The newly implemented Rainbow Baby program at Capital Health gives families who have endured the loss of a baby the chance to bring in a new life with empathy and care.

Complex feelings flooded Mary Richmond-Michael and her husband, Doug Michael, when they learned they were pregnant with their first baby—a girl they named Izzy. While the couple desperately wanted a baby, Doug’s 36-year-old brother, Steve, was dying of colon cancer during the same time period.

Steve passed away in the beginning of 2020, and when the COVID-19 pandemic gripped the world that March, the couple knew they needed to focus on the excitement of the new baby instead of on all the pain and suffering happening everywhere they looked. But on April 14, 22 weeks into her pregnancy, Richmond-Michael awoke in the middle of the night, like she often did. This time, however, something didn’t feel right. “I went back to bed and woke up at 4 and went to the bathroom again. I turned on the light, and there was blood,” she recalls. “I called the off-hours line, and the midwife called me back. She said to come to the hospital.”

As the couple hurried to Capital Health, Richmond-Michael began to feel intense cramping, and by the time she got to the hospital, she was completely dilated. Although the doctors and nurses did everything they could, the labor could not be stopped. Izzy was born shortly after and lived for about an hour. The couple held their baby girl, and she died in their arms. Richmond-Michael didn’t want to stay in the hospital, but leaving without her daughter brought unimaginable pain. “I felt like we were leaving her behind, cold and alone. It was such a horrible feeling,” she says through freshly shed tears.

Doctors were able to find the cause of Izzy’s sudden pre-term labor. The medical term, which Richmond-Michael absolutely hates, is known as an incompetent cervix (also called a cervical insufficiency), which is when weak cervical tissue causes premature birth or the loss of an otherwise healthy pregnancy.

Despite the new and frightening diagnosis, the couple started trying to get pregnant again almost right away. “I was obsessed with getting pregnant again,” she says. “You are in this mode of wanting to become a mom, and that doesn’t go away because you lose a baby.”

About 6 months later, in October of 2020, Richmond-Michael became pregnant again, this time with a boy. The couple was happy to be pregnant again, but the loss of Izzy and the concerns about her cervix made for an emotional and anxious pregnancy. “I was in therapy throughout the pregnancy. I had ultrasounds every week starting at 18 weeks. I was excited but also really scared. It got worse as it got closer to when I lost Izzy. I was kind of a basket case,” she says. “I was counting down every day until 24 weeks [when the baby would be viable]. It’s hard to just trust when you’re so anxious and emotional and your baby’s life is on the line.”

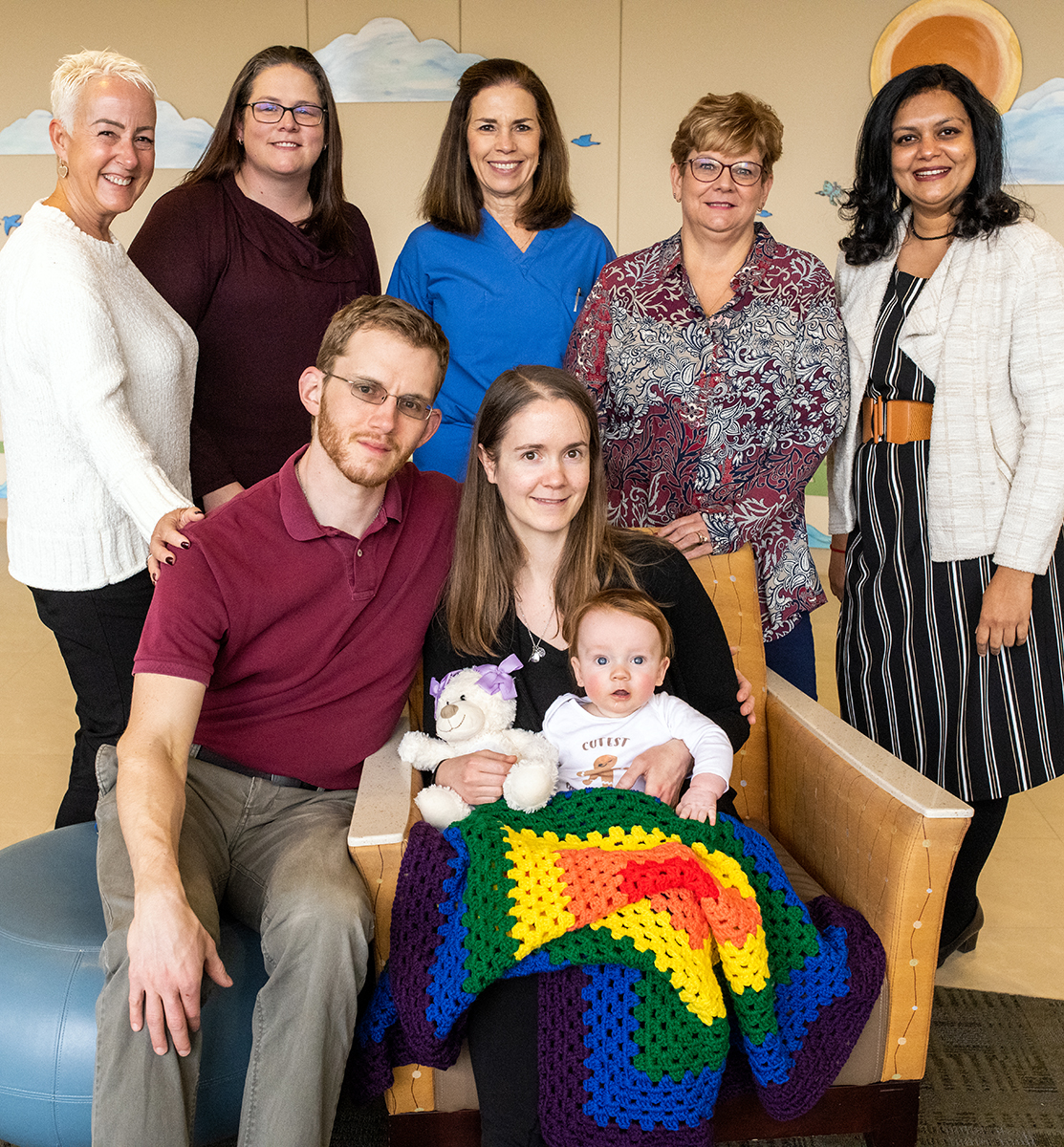

One thing did help. At about 8 months into the pregnancy, the couple was introduced to Joyce Merrigan, clinical specialist in maternal child health at Capital Health, who was named the 2020 March of Dimes Nurse of the Year in the Nurse Educator in Health Care Delivery category. She told them about a new initiative Capital Health was launching called the Rainbow Baby program, to help families who have experienced the loss of a child at or before birth. As it turned out, Richmond-Michael’s new baby boy, Ian, born at 34 weeks and 5 days, became the first Rainbow Baby born at Capital Health.

In our culture, we don’t talk about our babies that we’ve lost. For families, one of the enduring areas of grief is that nobody says their names and they don’t feel comfortable keeping their baby’s memory alive.

Joyce Merrigan

A Hard Truth

The shock of losing a baby can exponentially compound grief. Joyce Merrigan explains how we can avoid that by having the tough conversations.

Bereavement care is a specialty that requires training to gain knowledge of communication and specialty skills in the provision of authentic care to patients and their families experiencing pregnancy loss. When it comes to navigating grief, so much of what gets missed has to do with patient preparation and the open dialogue between doctor and patient that is too often forgotten or avoided.

A common narrative among families who experience loss is, “I didn’t know that my baby could die.” In fact, Richmond-Michael echoes that exact sentiment. “I learned the hard way that despite what you see on TV and in the movies, two lines on the pregnancy stick doesn’t always mean a baby in the end,” she says.

That’s why it’s critical that providers have this conversation (as difficult as it is) with every pregnant person, to raise awareness that babies do, sadly, sometimes die before or during birth. The first time you learn that a baby can die should not be when it happens to you. It’s also crucial that there be a focus on patient education upon discharge and resources provided for follow-up and emotional care. The Capital Health Multidisciplinary Perinatal Bereavement Committee includes members from many disciplines, including emergency medicine, obstetrics, chaplaincy, and social work.

At Capital Health, labor and delivery nurses are experienced in the delivery of expert, evidence-based perinatal bereavement care. We are proud of the work we’ve been able to accomplish throughout Capital Health to address these common gaps in care.

Angels & Rainbows

Merrigan, who chairs the Perinatal Bereavement Multidisciplinary Committee, spent 20 years as a labor and delivery nurse. That experience brought to light the specific needs for families around bereavement of their “angel babies” and the birth of new babies that many people don’t intuitively understand. “In our culture, we don’t talk about our babies that we’ve lost. For families who have gone through that, one of the enduring areas for grief is that nobody says their names and they don’t feel comfortable keeping their babies’ alive. That often leads to anxiety and apprehension surrounding the birth of a new baby,” Merrigan says. “Part of what the Rainbow Baby program does is give them a chance to share their story in a safe space and decide how they would like to include the story of their rainbow baby with their angel baby.”

Lauren Colman, RN, has been on both sides of loss—as a nurse and a mom—and she knows all too well how confusing it can feel to carry the sadness of a lost baby and the joy of a new baby at the same time. On September 3, 2010, Colman lost her daughter, Ella, when she was 39 weeks pregnant. “I stopped feeling movement one day. I went in, and the doctors couldn’t find a heartbeat,” Colman says. “Now I have three rainbow babies, but in the 11 years since we lost her, I never stopped thinking of Ella.”

The stigma of a lost child and the instinct to conceal the loss and avoid making others feel uneasy when you talk about it, is starting to lessen, although there is still a long way to go. “When I would try to talk about Izzy, it made other people uncomfortable, and that’s not something you want to do. Not being able to really talk about her, that part’s hard,” Richmond-Michael says.

Support Staff

Under the umbrella of the Rainbow Baby program, Richmond-Michael was able to request the presence of the labor and delivery nurse Galyna Mykhlyk for the birth of her new baby. That gave her comfort, since she was present and had facilitated Izzy’s delivery and care when the family gave birth to and said goodbye to their baby girl.

Merrigan says most moms request the same nurse as they had for the “birth of their angel baby,” which she says is not only comforting for the family but cathartic for the doctors and nurses as well. “As a staff, we have to remember what our role is for the family—to facilitate their grief journey. We have to give them the ability to say hello to their babies,” Merrigan says. “Usually when you lose someone you love, you can remember a smile or a joke they told. With a new or unborn baby, there are no memories. We feel good when we have a family that’s able to say hello to their angel babies. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t impact us emotionally. As a human, it becomes complicated sometimes. We don’t have a safe space to unpack those feelings.”

As part of the Rainbow Baby program, a printed rainbow is placed on the door of the mother’s room at Capital Health Medical Center – Hopewell to alert hospital staff entering the room of the complex emotions the family may be experiencing. One of the most important aspects of the Rainbow Baby program is the staff awareness of the loss the family previously endured. “It felt good to know that the staff knew because it’s a happy occasion, but it’s also sad,” Richmond-Michael says. “We knew we wouldn’t hear any of those well-meaning things people say that would be awkward or painful, like, Is this your first child?”

All the precautions and attention ended up being critically important because Richmond-Michael ended up needing an emergency C-section to birth Ian. He was born at 5 lbs, 7 oz, and although he was sent to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, he was ultimately a very healthy baby.

In the creation of the program, Merrigan recruited Capital Health’s volunteer services to donate time and talent to the Rainbow Baby program. Dipti Padillya, manager of volunteer services, says when she explained the program to her volunteer knitters, she had more than 10 sets of rainbow hats and blankets ready to go in just about 6 weeks. As a result of their efforts, newborn Rainbow Babies also receive onesies with a rainbow applique that reads “Handpicked for Earth by my [brother/sister] in heaven.” The family can also choose to personalize the onesies with the name of the family’s angel baby.

Along with the special gifts for Ian, the couple has a study in their house with the plaque from the hospital in Izzy’s name, along with a small box with her ashes. Richmond-Michael and her husband both wear lockets around their necks with some of Izzy’s ashes in them as well.

And they have Ian, their amazing redheaded Rainbow Baby. While both parents are incredibly grateful, Richmond-Michael admits the first 6 months of his life have been filled with anxious moments. “I worry about everything. I was worried about sudden infant death (SIDs) for a while. When you have a loss like ours, when you are a person who falls on the wrong side of statistics, you’re always concerned about something happening to your baby,” she says. “But if I could go back to when I was first pregnant with Ian, I guess I would tell myself to try not to worry so much—everything will work out. I don’t know if I would have listened because it’s easier said than done. But it’s something I needed to hear.”