In a culture that fears mortality, just the idea of losing a child torments parents and keeps them up at night. These moms faced that very nightmare, and now they are living in its aftermath. Here’s how they are growing through grief and how you can help them.

Sometimes it happens when we feel that first flutter or kick when the tiny being inside us gets her first hiccups. For others, it comes in a flood of emotion, after we labor and sweat and scream and push our infant into the world, seeing her red, crying face for the first time. But so often, it happens in the tiny hours of morning during a midnight feeding or when you’re soothing her back to sleep. You hold her warm little body in your arms, and it’s just you and her in the stillness of night. You stare down at her, memorizing her face and gently touching her miniature, balled up fingers and toes—pieces of you—and you actually feel your heart clench and grow inside the suddenly tight cavity of your chest. The love is so big it almost hurts. And that’s when it happens.

You reflexively make two promises to your child. The first is an oath to love her for all time with every fiber of your being. The second promise is heedless of all the forces that are out of our control, but it’s the kind of wishful thinking that’s impossible to avoid. You swear to love and protect her against anything and everything that should ever try to harm her. You are her parent, and you will keep her safe.

And so, when she takes her last breath, when you lose her unexpectedly to an illness, a tragic accident, or a heinous crime—when you bury your child—you suffer the cruelest, most insidious loss, one that will take you apart all at once and piece by piece. But you also have to endure the guilt and torment of what feels like a broken promise. Losing a child causes a tidal wave of grief that leaves no part of you untouched.

For supporters and bystanders, the fear around death, especially as it relates to children, often makes us look away or run and hide, leaving the bereaved feeling isolated and misunderstood. For help and answers on surviving and rebuilding after such a painful loss or for supporting loved ones who are enduring one, we had intimate conversations with women in our communities who faced the death of a child and continue to feel the wrenching pain. We also asked for help from Joe Primo, CEO of Good Grief, a nonprofit that shepherds people—particularly children—through grief every day and works toward emotional literacy around loss. “Very few people will understand the depth of the pain and the complexity of the feeling that comes with losing a child. And that’s a very isolating thing,” Primo says. “In reality, grief is a part of the human experience. But we have a breakdown of communication, a breakdown of our ability to transfer wisdom of how we heal and how we rebuild.”

We as the bereaved need to know that we matter and that our children mattered. A parent wants to know that even though their child lived only 6 years, he will be remembered.

No parent would ever choose this. You have to learn to forgive yourself. You did the best you could with the information you had at the time. You loved your child unconditionally and continue to love your child.

We Are Overcome

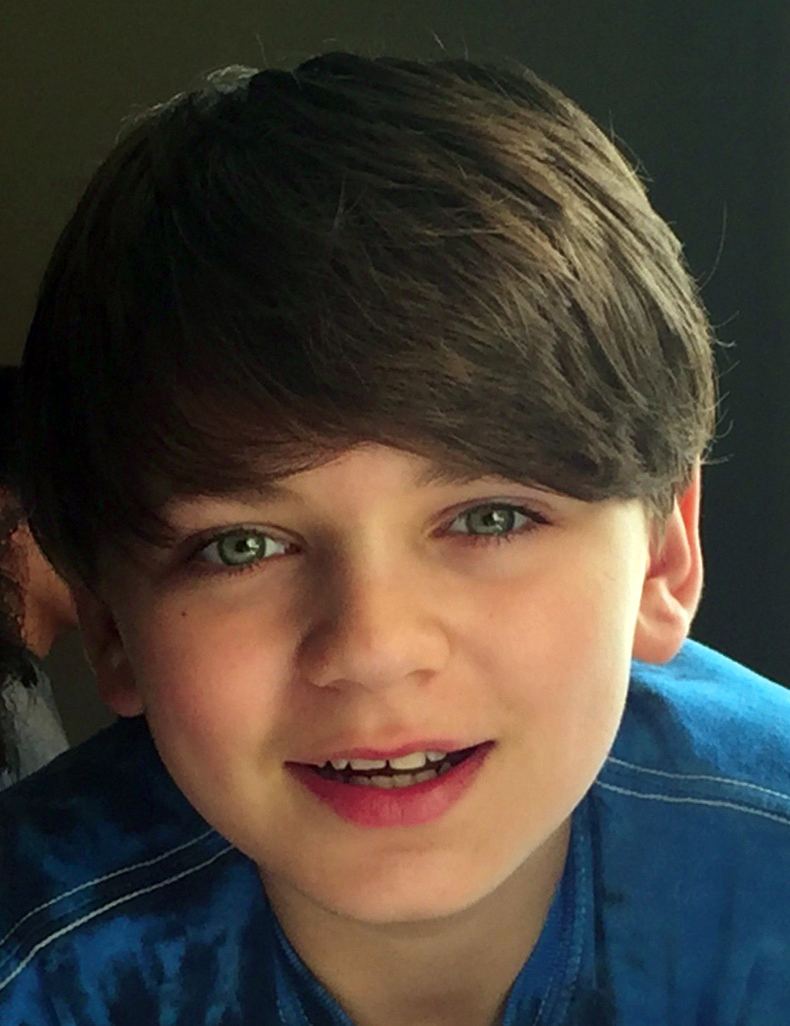

In September 2016, the beginning of the school year was chaotic, as it always is for Evelyn Bardzilowski’s family. Ella was 10, Owen was 14, and her oldest son, Miles, was 17. Just a week into school, Owen told his parents his bike was stolen, and he wasn’t sure how he’d get to school the next day, so they went looking for it. When Evelyn and her husband returned home empty-handed, Owen, who Evelyn describes as smart and funny and the kindest person she’s ever known, told his mom not to worry; he’d ride his skateboard to school the next day. “He told us how much he liked his classes at school, and he went back to his room to do his homework,” Evelyn says. “The next morning, my husband left for work, and when I woke the kids up for school, Owen had taken his own life.”

Friends, family, and the community rallied around the Bardzilowskis, and she found herself in what she describes as a “hurricane of support,” a swirl of cards, notes, gifts, and pre-cooked meals, every bit of which she needed as even the simplest tasks became impossible.

The pain and sadness—the self-ridicule—was overwhelming for a long time. Time helped. Being present with her other children was medicine. Letting herself feel emotions and not trying to cover her pain was crucial. And Good Grief gave her the kind of support and tools she needed to begin to forgive herself. “I’ve learned that it doesn’t matter how your child passed—every mother blames herself. It’s just who we are and what we do,” she says. “But it’s so important to remember that you would never have chosen this death for your child. No parent would ever choose this. You have to learn to forgive yourself. You did the best you could with the information you had at the time. You loved your child unconditionally and continue to love your child.”

Evelyn says grief doesn’t have an expiration date—she misses Owen acutely every day. But there are days when she finds peace, and she makes happy memories with Ella and Miles and her husband. But sometimes the grief attacks out of nowhere. “Almost every grieving mother I know has had a panic attack or meltdown at the grocery store at one point. Out of nowhere, grief grenades get lobbed at you from across the cereal aisle,” Evelyn says. “You reach for their favorite cereal instinctively, only to remember harshly that you will never need to buy that particular kind of cereal again. It is excruciating. And it happens still.”

Ocean of Grief

Eight-year-old Dominic Liples was a responsible, old-soul kind of kid, due in part to the fact that his younger brother, Ciarlo, was born with spina bifida, a birth defect that occurs when the spinal cord doesn’t form properly, leaving him paralyzed, which the family discovered in utero. One morning in March 2016, it was time for the bus to come, and Dominic didn’t have his shoes and socks on. “He told me, ‘Sometimes I don’t like to use my left arm,’” she recalls. “When he got off the bus after school, he was dragging his foot. At first, doctors thought it was Lyme’s disease, but the CT scan showed there was a mass in the thalamus in his brain. The oncologist came into his hospital room and started to cry when she delivered his official diagnosis, and she said he would need a miracle to survive.”

Dominic had surgery 2 days later and started an aggressive course of chemo and daily radiation. When doctors realized the treatments were ineffective in fighting the tumor, Dominic began receiving immunotherapy, which wasn’t being used at the hospital for brain tumors at the time.

While Dominic’s medical team never gave the Liples family much hope, they did everything they could to work a miracle. The family built a website (prayfordominic.com) and began raising money for research toward a cure under the Pray for Dominic Hero Fund. The Liples’ hometown of Doylestown, Pa posted signs throughout the community that said PRAY FOR DOMINIC on storefronts and on the movie theater marquis in the center of town. “We figured we had a year at least. But less than 9 months later, he was gone,” Kira says. “The thalamus has very little room for swelling. The swelling is what killed him.”

He died December 7, 2016, at 8 ½ years old. Some of the signs remain around town, including a picture, drawn by Dominic, in front of Monkey’s Uncle. Those kinds of little things matter to Kira now. “The core group of friends is still here, but the majority of people are long gone. Since Dominic died, my friends do random acts of kindness for our family—dropping off a plant or some cookies every day in December. It’s made us feel remembered. Memories that pop up unexpectedly—those are the hardest days,” she says. “Grief is like waves like you’re in an ocean. You’re swimming along and then a birthday might trigger a wave that crushes you.”

This was not supposed to happen. Nothing compares to this. Every day, you wake up and it happens again. It’s not just a nightmare—it’s your reality. But we try to find joy in everything we do. We are living because Dominic can’t.

The Lasagna Effect

Joe Primo has seen this so many times. When someone dies, especially children, people want to do something to help.

But we have to be careful not to fall into a common trap of offering tangible support early and then fading away.

There are a lot of people who throw sympathy at you (often with a lot of lasagnas), and then there will be a lot of drop-off. “Lasagna is something tangible you can offer. But what matters even more is what you do 3 months later, offering a conversation and asking how they are doing that day,” says Primo. “There’s so much fear around saying the wrong thing. But remember this: even when we say the wrong thing, people are very forgiving if we are well-meaning and consistent in our actions.”

Remember Them

For those of us supporting the bereaved, it’s important to know that while we may be well-intentioned, avoiding conversations about their lost child is the opposite of what they need. “Say their names. It’s the best gift you can give a bereaved parent. This is how you can support someone who is grieving. It means everything. It’s music to our ears. It validates, they lived,” says Angela Miller, best-selling author of You Are the Mother of All Mothers, and founder of ABedForMyHeart.com, a grief support hub for millions of grieving parents.

Angela lost her son, Noah, when he was just 2 ½. “People recoil when they hear about the loss of a child. Our culture is extremely grief-illiterate—we don’t know how to support hurting people, especially bereaved parents. I’m every parent’s worst nightmare,” Angela says. “I became a reminder for people that children can die, and they do.”

After Noah’s death, Angela was on the receiving end of the stigma and isolation that often results from the fear many of us carry about mortality. She promised herself if she made it through the unbearable, she would dedicate her life to supporting grieving parents. She began creating the resources she wished she had when she was going through the worst of it, including books, articles, grief support groups, retreats, a website, and the A Bed For My Heart grief center in Minneapolis.

Her most important piece of advice is to help grieving parents keep their children’s memory alive, she says. Acknowledging the absence of one of the most important parts of someone’s life can actually save them, says Joe Primo. “We as the bereaved need to know that we matter and that our children mattered. A parent wants to know that even though their child only lived for 6 years, he will be remembered,” he says. “The ability to share about the child is the most important thing.”

That’s why, around the December holidays—the month Dominic died—the Christmas tree in the center of Doylestown and the front door of his elementary school are adorned with giant neckties. As a small child, Dominic asked if he could put a tie on the family tree because he wanted to “make it look handsome.”

Seeing those neckties is bittersweet, Kira says, and they bring her joy because her son is remembered. Her younger son, Ciarlo, who is now older than Dominic was when he died, calls this feeling “sappy—a little sad, but also happy.” “We are all sappy,” Kira says with a small laugh. “He will always miss Dominic. Like we will always miss him. This was not supposed to happen,” she says. “But we try to find joy in everything we do. We are living because Dominic can’t.”