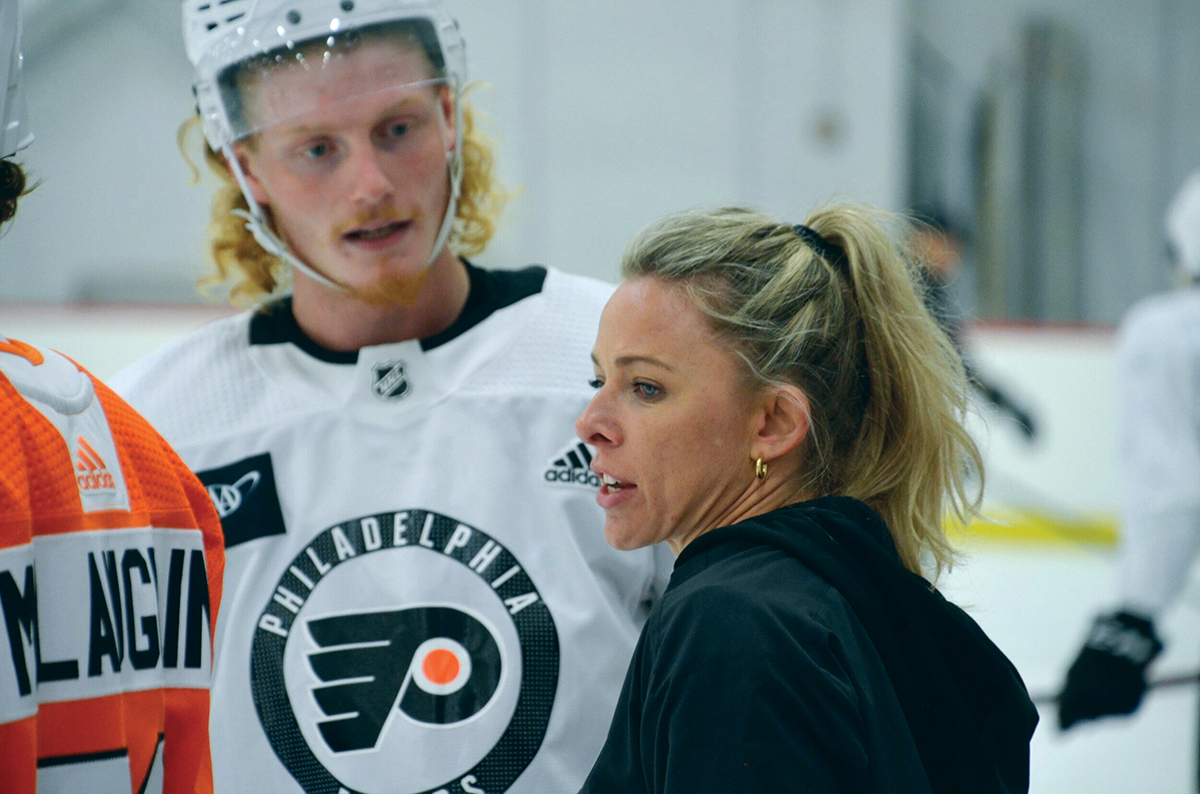

The head coach of the Princeton Tigers models resilience and guts on and off the ice.

When you’re the only girl in your family growing up poor in a town called Hensall, a community in Bluewater, Ontario, Canada, with a population of 1,173 people, finding ways to entertain yourself takes a bit of creativity. “Growing up in such a small town, there was really nothing to do,” says Cara Morey, head coach of the Princeton University Women’s Ice Hockey team.

“We were 45 minutes from a mall and 45 minutes from a movie theater. We didn’t even have a high school. I never felt like I fit in because when I was young, girls weren’t really athletic. I didn’t want to play with dolls. I didn’t want to do the stuff the girls were doing. I just wanted to play sports.”

So from grade school on, she played sports—eight, to be exact. And in Canada, in a household of boys, hockey is practically a religion. “Everybody played, but there was no girls’ hockey when I was little, so I played with the boys until I was 9,” she says. “I was always having to keep doing more and keep pushing harder—that was the mentality of my parents and my brothers and my small-town upbringing.”

With very few opportunities for girls in hockey, Morey competed in ringette, a noncontact sport played in a rink with hockey skates and a straight stick with no blade at the end. She played ringette at the highest level and competed in the Canada Winter Games, but she was “kicked out” when she body-checked an opponent. By that time, meaningful efforts to change the rules for women were altering the landscape toward inclusion in ice hockey.

Morey, 45, grew up in the 1980s and 1990s, just as hockey player Justine Blainey was immersed in her fight against gender-based discrimination, which included five court cases and a hearing with the Supreme Court of Canada in 1987 (which she won). “So when I got kicked out of ringette, I decided to switch to hockey,” Morey says. “I figured, ‘Okay, I can make my dad proud.’ And within my first tournament, I was getting recruited to come to the U.S. to play hockey.”

I never felt like I fit in because when I was young, girls weren’t really athletic. I didn’t want to play with dolls. I didn’t want to do all the stuff girls were doing. I just wanted to play sports.

Meaningful mentor

Morey committed to Brown University, an Ivy League school in Providence, RI, to play field hockey and ice hockey, a decision that changed her life and set her on a trajectory to play hockey at the highest level. At the time, women’s hockey wasn’t officially recognized by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), a relatively new development, in the year 2000. But Brown’s women’s hockey program started in 1960 and was one of the most competitive in the country at the time. “I found out that [the players] got to keep their gear at the rink and that they had their own locker room, and that was enough for me,” Morey recalls. “I was like, I am going there. Brown was one of the best in the country, and that was the place where I felt like I made it to the big time.”

When she got to Brown, Morey, who had never heard of the Ivy League, quickly realized the extent of the opportunity in which she found herself. She made the most of the chance in the classroom by studying human biology and in hockey rink. “I took a lot of anthropology and women’s studies classes, and I became a massive feminist without knowing it was happening,” she explains.

But she also absorbed as much as she could from Brown’s longtime coach, Digit Murphy, a fierce advocate for women’s sports (especially hockey). Murphy, who proclaims her purpose in life “is to create new opportunities for women to grow, lead, and be more successful in sports, work, and life” became an inspiration and mentor whose lessons propelled Morey as an athlete and, eventually, as a coach and leader. “She was a strong female leader, and she was dynamic and loud, and I learned so much from her,” Morey says. “I was a budding feminist without knowing it, and Brown and [Digit Murphy] really brought that out in me.”

Drop the Puck

Even though opportunities to play women’s hockey were few and far between, Morey continued to play at the highest level—she was a gold medalist with Canada’s National Women’s Under-22 Team at the 2000 Nations Cup, in Füssen, Germany.

But then she experienced her first major disappointment. Morey was the last player cut from the 2002 Canadian team, who played in the Salt Lake City Olympics (the Canadians ended up beating the U.S. 3–2 to win the gold). “I had never been cut from many things, so when I got cut from the Olympic team, I thought that was the end of my sports career,” Morey recalls. “Now they support women much better when they’re training for the Olympics, but back then you really couldn’t work much because you’re training and there was no financial subsidy. So you basically had to live in your parents’ basement.”

So Morey pivoted away from sports, hanging up her skates and focusing on getting her master’s degree from McGill University in Montreal. At the time, her husband, Sean Morey, a fellow athlete who she met at Brown, was trying to make an NFL roster, but he kept getting cut from camps. But then, finally, Sean Morey signed with the Philadelphia Eagles in 2001, and he became the special teams MVP with the Birds that year.

Morey, whose maiden name was Gardner, hadn’t changed her name at that time, because she so valued the name on the back of her jersey. Suddenly, while her husband’s athletic career took off, Morey’s became uncertain. “I was super proud of him. I didn’t feel competitive with him, but it’s hard losing your identity—my name became ‘Sean’s wife.’

As the couple had children—daughters Devan, Kate, and Piper—Morey focused on taking care of the family during her husband’s football career with the Philadelphia Eagles, the Pittsburgh Steelers, and the Arizona Cardinals. “It was hard because we never knew where he would end up—he was always on a 1-year deal. So I would move back to Toronto with the girls every offseason until he made a roster, and then I would pack them all up and head to the new place. We moved 14 times before we ended up in Princeton,” she says. “I love my kids. I love cooking, and I clean as a stress reliever. But being a stay-at-home mom was really hard for me. I needed something else in my life.”

The Consummate Coach

While she was in Pittsburgh, Morey was looking for opportunities to stay involved with hockey. She found Robert Morris University in Pittsburgh, where she volunteered on Tuesdays when Sean was off from the NFL. When they moved to Arizona, Morey earned a second master’s degree and coached the Phoenix Lady Coyotes U-19 AAA team. And then Sean retired. “We were both at home for a year, and I was like, ‘Well, this isn’t going to work—I’m gonna get a job,’” Morey says.

With her three girls all under the age of 7, they moved the family to Princeton, NJ. She started at Princeton as an associate head coach in 2011, and Morey was announced as head coach on June 12, 2017. During her tenure as coach, the team won its first ECAC tournament title and an Ivy League championship, qualified for two NCAA quarterfinals, set the program single-season wins record, and is regularly included in the top-10 rankings.

Nothing could be a more natural fit for Morey than coaching young women to play hockey and develop courage and grit. Not only does she still show up at the rink every day with a burning desire to win, but she also wants to help her players become great leaders and exceptional humans. “I always knew I wanted to inspire and make an impression on young women,” Morey says. “I knew I’d be close to my players, and I am. The biggest thing people don’t understand is that there’s never an off day in coaching. If one of my players calls me at 11 p.m. because they need something, I’ll be there. That’s the responsibility you take on when you have 18-year-olds and 20-year-olds leaving home for the first time and they need somebody to be there for them. That’s me.”