Leslie Gudel’s life took a sudden turn in 2014 when her 10-year-old daughter had a stroke. She launched a not-for-profit to help other AVM and aneurysm survivors. Now, 6 years later, both mother and daughter are reinventing themselves yet again.

Kendall Kemm didn’t know how to tie balloons until her neighbor taught her on an October night in 2014. Having finally mastered the trick, the 10-year-old sat happily for hours, blowing up balloons for her mother’s Halloween party and artfully knotting them. By night’s end, she’d lost sensation in her hand but went to bed unconcerned, chalking it up to overdoing her newfound skill.

But in the morning, Kendall was weirdly uncoordinated, her hand still not right and now her foot was suddenly not cooperating. Kendall went to walk to her desk, where she’d laid out her softball uniform the night before, and she stumbled. She near face-planted while retrieving a bottle of water from the fridge. She casually mentioned it all to her mother, Leslie Gudel, as the two drove to a softball tournament. “I don’t mean to complain, but my foot isn’t working’’ is how Leslie remembers Kendall phrasing it.

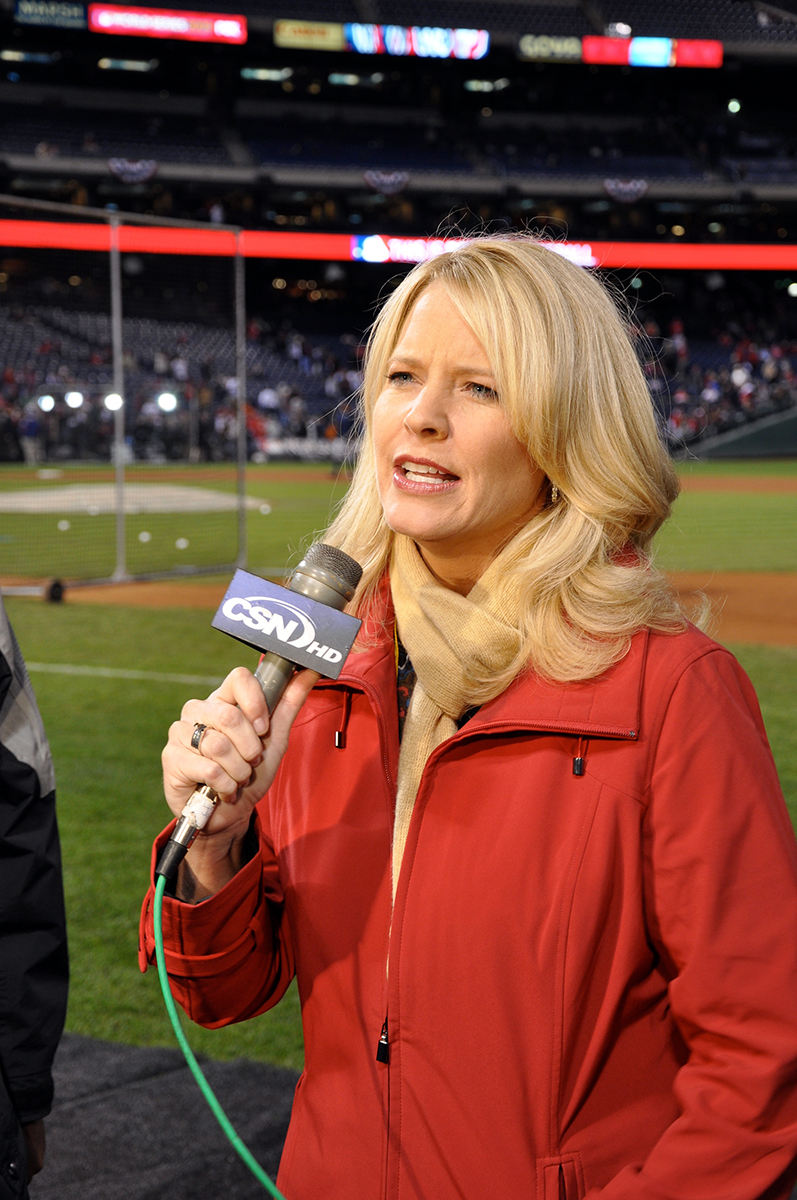

By then, Leslie was in the first stages of a career pivot. Hired in 1997 with the launch of Comcast SportsNet, she debuted as a pioneer, the first full-time female sports anchor in Philadelphia history. However, the shelf life for such a gig isn’t endless, and by 2014 Leslie worked as the network’s Phillies reporter, after asking her bosses to reduce her role after she created her own small business. The practical Leslie understood how these things went, and she held no bitterness. She loved baseball, so the new job suited her professionally. It also allowed her more time with her children, Kendall and her younger son, Chase.

Her offseason weekends were often filled, just like the one on Saturday, October 25, 2014, with Leslie chauffeuring her daughter to a tournament. Though she was still in elementary school, Kendall already dreamed big when it came to softball. She wanted a Division I scholarship, and she committed herself fully to the practices, clinics, and tournaments necessary to achieve it. “It was my whole life,” Kendall says.

By dinner time that evening, Kendall’s whole life changed forever. So did her mom’s.

While Kendall’s Crusade didn’t become an officially registered nonprofit until 2016, it was born that October day in 2014, as Leslie feverishly tried to find answers after doctors explained to her that her 10-year-old daughter just had a stroke.

Life on the Edge

If you’ve ever tried to untangle a web of Christmas lights, you have a working knowledge of an arteriovenous malformation, or AVM. They’re a maze of jumbled blood vessels that though unnecessary to live, can be deadly. They mess up the normal blood flow—where arteries take oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the brain, and veins carry the oxygen-depleted blood back to the lungs and heart. More troublesome in their jumble, they often weaken but typically go undetected until a catastrophic rupture causes a hemorrhage, or in Kendall’s case,

a stroke.

In hindsight, Leslie and Kendall have surmised that all of that balloon blowing put the pressure on Kendall’s AVM, causing it to burst. In all likelihood, the bleed started while she slept. But as Leslie drove to the softball tournament, she knew none of this. She almost nonchalantly asked a friend to check on Kendall’s suddenly balky left leg. Only after that friend ran her fingers down her shin and Kendall said it felt different did mother and daughter hightail it for a nearby hospital. By the time they got to the parking lot, Kendall couldn’t walk unassisted.

In the ER, Leslie overheard a nurse describing Kendall’s condition, repeating something about a flat left eyebrow. So she called up a friend who was also a neonatal specialist and relayed Kendall’s symptoms. He warned her to brace herself for bad news. Soon Kendall was in an ambulance bound for A.I. duPont Children’s Hospital in nearby Wilmington, Del. After doing an MRI on Kendall’s brain, doctors explained that Kendall had an AVM. “The first words out of one doctor’s mouth was, ‘It’s a rat’s nest in there,’” Leslie says.

After Kendall spent 12 days in the hospital recovering from the stroke, the doctors saw little hope for ridding Kendall of the AVM. “They basically told us to go and live our lives, that if they did anything, it would leave her devastated,’’ Leslie says.

Kendall is now 17, a high school senior, applying for college. She does not have the use of her left arm and has a hitch in her left-footed giddy-up but she has played softball anyway, and recently taught herself how to play golf with one arm.

Kendall is far from devastated. Her AVM is now 95 percent gone. Her doctors at Stanford University obliterated the AVM to near extinction, but they only got there thanks to Leslie’s determination and the gracious strength of a young woman who didn’t know how tough she was until she had to be.

I knew I was strong, but I didn’t appreciate what little fear I had about trying new things. I always knew you didn’t have to be perfect to be successful. If you bat .300, you’re in the Hall of Fame. Now I’m embracing that.

Painful Choices

After that first group of doctors laid out a bleak outcome for Kendall, Leslie put her journalistic shoe leathering to work. She learned that one in 5,000 people have an AVM and of those 5,000, four in every 100 will suffer a hemorrhage. But information was spotty, particularly in pediatric cases. Doctors in both Philadelphia and Boston apologized but offered no solution, all reiterating that this would be the family’s new normal. Leslie refused to accept that, understanding that as long as the AVM rested in her daughter’s brain, there was a danger of another rupture.

She scoured the Internet for information, searching not just medical sites but support groups. She found her biggest allies among fellow parents—one father in Virginia shared studies he found after diving down a rabbit hole following his own child’s diagnosis. Leslie set up two computer screens in her house, one with case analysis from the National Institute of Health, the other with Google Translate, to help explain all of the medical jargon.

In the meantime, Kendall improved enough to go home and even return to sports, the use of her hand and leg returning. But Leslie knew they were merely buying time.

She kept reading and researching, eventually introduced to Steven Chang, MD, the vice president of strategic development and innovation in the department of neurosurgery at Stanford, who gave Leslie the response she longed to hear. “We can help.’’ Dr. Chang and his staff, however, cautioned Leslie that the treatment was not without risks, and the radiation could do its own damage. To Leslie and Kendall, though, there was little choice. “Someone said to me, ‘it’s like hooking a garden hose to a fire hydrant. Eventually it’s going to rupture,’’ Leslie says. “We had no choice. We couldn’t just sit around and wait.’’

On February 4, 2015, Kendall underwent her first of what would be three intensive radiation treatments. The second came that July, and in less than a year, the AVM had shrunk by 80 percent. The doctors’ worries, however, were realized. The radiation cost Kendall the use of her left arm, robbed her of a quarter of her vision and left her with a limp in her left leg—relatively small sacrifices compared to what a rupture could do, but sacrifices nonetheless.

Then more bad news compounded the good. In the spring of 2016, Comcast SportsNet informed Leslie that the upcoming Phillies season would be her last. Though never one to define herself by her career, others certainly did, and with the parting so public, she naturally felt the sting of rebuke. Ever optimistic, she tried to find the light—her last day, for example, was the same as Phillies star Ryan Howard. “Sometimes the best decisions are the ones made for you.’’

She also had the constant reminder of perspective in the form of her daughter. Just after Christmas in 2018, Kendall suffered yet another small stroke, an MRI revealing that her AVM had, as Leslie put it, “recruited new veins.” Her third and final radiation, in January 2019, concentrated on that new growth, finally eviscerating much of the lesion altogether. “In May, when her doctor told us the AVM is 95 percent gone, it was the first time I could honestly say I saw a light at the end of the tunnel,’’ Leslie says. “I never allowed myself to even think that way. I always pictured her having to deal with this in college and forever. Now it’s almost gone.’’

Paying It Forward

Mother and daughter have finally allowed themselves to think about the future. After her SportsNet career ended, Leslie worked as a realtor as a stop-gap. But it wasn’t until recently that she actually asked herself a simple question: What do you really love? The answers, she discovered, were building things and helping people.

Kendall’s Crusade proved that to her. In the throes of their own experiences, Kendall and Leslie launched the not-for-profit, turning Leslie’s quest for a treatment into an informational roadmap for others. She put her Philly resources to work, and with donations, the organization raised more than $100,000 in its first year. “I knew I was strong, but I didn’t appreciate what little fear I had about trying new things,’’ Leslie says. “I always knew you didn’t have to be perfect to be successful. If you bat .300, you’re in the Hall of Fame. Now I’m embracing that, and my favorite thing that I tell people all the time is ‘If you don’t ask, the answer is no.’”

The not-for-profit is chugging along. Last summer, Kendall’s Crusade hosted a Disable AVM Golf Tournament, challenging golfers to a 9-hole scramble with a twist: Participants had to play with one arm, like Kendall does.

But not one to do just one thing at a time—she is a woman with an Emmy and three patents—Leslie is now dipping her toes into athlete representation. With name, image, and likeness legislation creating sweeping change in college sports, finally allowing athletes to profit, she saw a niche where her sports background and mama-bear skills could merge. Leslie intends to build relationships with athletes that offer protection as well as growth potential. “We want to make sure athletes don’t fall off a cliff at the end of their playing career,’’ she says. “This is everything I love—sports is about building things and helping people.’’

At 17, Kendall is reconciling what she has experienced. Through much of her battle, she was either too young to understand or too focused on getting better to think much about what it’s all cost her. She admits she’s just finally allowing herself to grieve what she lost. Discussing the prospect of going to college with her mother one day, she explained that she doesn’t want to necessarily go to college and get drunk, but she’s angry that her AVM has robbed her of the choice to try it. She watches, almost jealously, as people go about their everyday lives and movements—the ability to carry a drink and hold a phone simultaneously or use two hands to swing a baseball bat. “I used to do that,’’ she says. “I forget what it’s like to have two hands.’’

During middle school and high school, she was dogged by the cruelest fate for a teenager—the misery of being different. Kids stared when she had to roll up in a wheelchair or as she adapted to life with one hand. Traditional teenage life rites—getting a driver’s license, for example—have come and gone without her, and her softball dream is over. “For a long time, I’d walk out the door and put on a fake smile,’’ she says. “I still struggle with that grief. I still get angry.’’

But she is quick to insist she’s not going to wallow. “I want to focus on my goals, not what’s happened to me,’’ she says. The start of college serves as the perfect segue, a chance for Kendall to reinvent herself. She dreams of being a broadcaster—but in entertainment, not sports like her mom—but she is as excited about the simple pleasure of spreading her own wings as she is pursuing a future career. “I’m scared,’’ she says. “I won’t hide that. But I’m also ready to live the rest of my life, without my hand being held.’’

Leslie feels the trepidation of seeing her firstborn off—especially since Kendall isn’t looking at any colleges close to Philly. But she is also eager to allow her daughter to have experiences on her own. “We’ve hovered the last 6 years, and in so many ways, she wasn’t able to grow,’’ Leslie says. “I’m not sure I would have felt this way 10 years ago before all of this happened, but now I want her to go someplace where she can’t turn to me for the answers. Make friends, fail, blossom, and become your own person.’’