Public service and self-expression don’t often go hand in hand. But this Trenton artist and firefighter believes she can do anything, and she wears the hats to prove it.

There’s no one medium that can fully reveal Bentrice Jusu’s humanity. Not her visual arts. Not her sculptures or murals. Not her documentaries or her poetry. Her activism can’t fully reflect it. Risking her life in service of others doesn’t completely define it either.

Thirty-year-old Jusu is a multimedia artist and activist. She’s a photographer. She’s a teacher. She’s a poet. She’s also a firefighter assigned to Engine Co. 3 in Trenton. If you ask her how she got here, she’ll probably laugh, the kind of laugh that starts in her belly and bubbles up through her shoulders to her face and her eyes. She’ll laugh because, just three decades in, her life has been a whirlwind of magic and tragedy, and she’s doing everything she can to spin that paradox into something beautiful and inspiring. She is weaving a tapestry that is so vibrant and varied that most of us can only admire it, learn from it, and let her colors brighten our own lives.

Journey to Self-Expression

Jusu was the second of seven siblings born in the United States after her family emigrated from Liberia. Her dad, who wanted to be a lawyer, had to drop out of law school to support his family and discovered a bit of luck when he “stumbled upon a massive load of roller skates.” Inspired by the movie Roller Boogie, her dad started a roller-skating company in Liberia, bringing along hundreds of kids, teenagers, and young men, Jusu says. “Then he came to Chicago in the 1970s on a visa to start a roller-skating company here. He was homeless for a while and then he found his way to New Jersey. When he saved enough money, he sent it to my mom so she could come with my siblings. A couple years later, I was born.”

Although the Liberian community in West Trenton was close-knit, Jusu says the neighborhood she grew up in, on Hermitage Avenue, was rough. “You have to go through a certain part to get to the schools,” she recalls. “But fortunately, my father would drop us off religiously every single day of my life.”

While her parents could be strict about being responsible and neat, they also encouraged their children’s self-expression. When Jusu was 3 or 4 years old, she drew a picture of her dad, which he hung in his closet so it would be the first thing he saw every day. Later, she drew a sketch of a movie on the wall of the living room, which her mother never erased. “It was there for years, this little doodle,” Jusu says. “She kept it there. She could have painted over it easily because my mom is meticulous like that, but she didn’t. To me, that was their embrace of the idea that I could express myself, especially through art.

“From early on, I looked at the world through art. Music wasn’t just a hobby or something you listen to. It was about, ‘What are these people saying?’ Images and pictures, it became like a puzzle. I didn’t see it as an option. This is how I’m supposed to be looking at the world.”

Jusu attended Trenton Central High School, and even though she showed athletic ability, she quit the basketball team to focus on her poetry. During her senior year, her advisor suggested applying to Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, NC, and when Jusu learned that SATs were not required and that American poet, memoirist, and civil rights activist Maya Angelou taught there, she was sold.

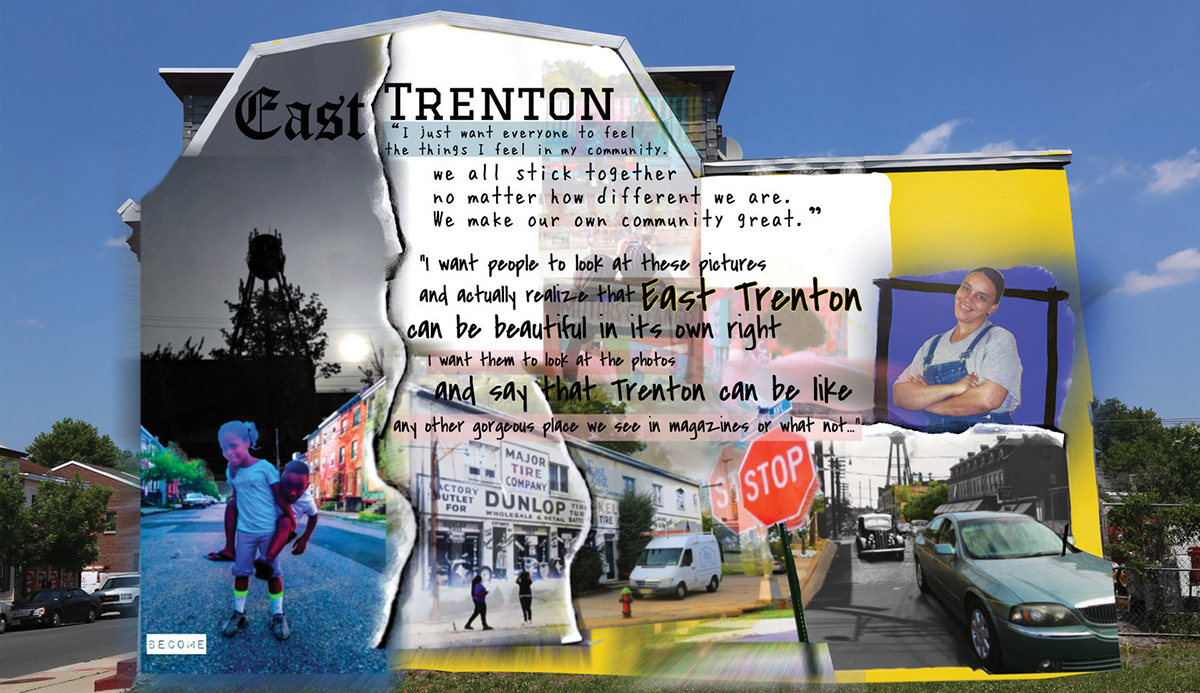

Art of Becoming: A Mural, by Bentrice Jusu

Not everybody is willing to take that risk to run into a burning building where they could die. And I say that humbly. But there are different kinds of risks. There’s the risk of danger and the risk of betting on yourself.

The Potential Project

As Bentrice Jusu marinated in how it felt to experience the terror at Pulse nightclub and lose young people in her life to gun violence, an idea began to form. She sensed the gravity of all the lost potential of those young lives. Out of that, Jusu created The Potential Project. In partnership with the Trenton Health Team, Jusu set about creating

public art throughout Trenton to celebrate the lives of victims. The goal is to encourage the hard and painful conversations required to heal our communities and work toward alleviating gun violence. “The Potential Project illustrates the life and the possibilities of those who are tragically taken by gun violence or violence in general, whether that’s due to preventable deaths, anger, or unprocessed anger from other people. We need to assess why it’s happening in these neighborhoods, in these communities. What is going on? But also, let their lives not be lost in vain, and let’s celebrate them through art.”

For more information on The Potential Project, visit potentialproject.art.

Following Her Art

During her sophomore year at Wake Forest, Jusu built an organization called Both Hands, which helped teens, regardless of personal background or level of experience, find their identity and potential through art. With support from a variety of funding sources, Jusu brought Both Hands to life. “The craftsmanship, the impact that artistry is and has on humanity is crazy, and there needs to be more institutions and support systems in place for kids, teens, and young adults. That was my dream, and that’s what Both Hands was.”

She dedicated her life to Both Hands Artlet for 7 years, partnering with the Boys & Girls Club to provide a safe space for teens in the Trenton area. While she thrived on the work and the opportunity to mentor young people, a series of traumatic events soon brought Jusu to the brink.

In June of 2016, Jusu flew down to Orlando, Fla. to celebrate her birthday with friends. On Saturday night, they went to Pulse nightclub, and they danced late into the night. Jusu and her friends were among about 300 people in the club at 2:02 a.m. when they heard gunfire. “Everybody went to the floor together when we first heard the shots, and then it went silent, silent and dark. Honestly, I don’t remember if it was because my eyes were closed or because the lights were actually off,” she recalls. “Then we got up and ran to the exit in the back, but there was a vending machine blocking it.”

As chaos erupted inside the club, bodies being trampled as they tried to evacuate, a few of Jusu’s friends kicked out a fence to open a small space that was wide enough to squeeze through. They’d escaped what was, at the time, the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history. Fifty people (including the perpetrator) were killed and another 53 were injured. “When we got back to the hotel room, we cried—we were in shock. But we didn’t realize how bad it was. We turned on the TV and saw Pulse on the news,” Jusu says, her voice strangled with emotion.

As devastating as the Pulse shooting was, that was just the beginning of a series of traumatic events that changed the course of Jusu’s life. “It was a rough time. My house burned down. I was dealing with a private lawsuit from Wake Forest because I couldn’t pay my student loan. One of my students, Jahday Twisdale, was shot and killed. He was 16. My childhood friend Cameron was killed. My dad developed early-onset dementia,” Jusu explains. “It was a lot going on that year, and that was my first bout of depression.”

Finding the Fire

While Jusu knew she still had so much to give, she also knew she couldn’t keep teaching for Both Hands. Emotionally and financially, Jusu was running on empty. “I couldn’t fill my babies’ cups anymore,” Jusu says of her students. “I wasn’t myself. I hated that I had to do that, but I had to.”

Although Jusu is still working in therapy to excavate some of the pain and work through the trauma she endured, she also had to address her other issue—art wasn’t paying the bills. Jusu was in the process of helping a student named Corey Rowell start the process of becoming a firefighter. She was in Starbucks, looking over the application, and the wheels began to turn. “[My friend Ray] put the spark in my mind that I could be a dope firefighter. I was a full-time artist, but I wasn’t able to support myself financially. I was basically homeless,” she says. “So I

told Corey, let’s do this together.”

Jusu did well on the entrance exam for the Trenton Fire Department, and she was hired in late 2019. All she had to do next was get through the fire academy. But life as a “probie” (probationary firefighter) was incredibly taxing, challenging Jusu physically and mentally every single day. “You wake up at 4 o’clock in the morning knowing we’re about to be drilled to death. You’re about to do the most intense exercise of your life. You do ropes; flip tires; do push-ups and sit-ups. You run. It’s all for a purpose because you literally have to use everything in you to run up and down eight flights of steps with 120 pounds worth of gear on,” Jusu says. “We studied fire science, talked about HAZMATs, and biology. You have hours of homework, knowing the information you are learning is life or death.”

While less than 5 percent of firefighters are women, Jusu says being a firefighter, going through the training, and preparing her mind and body to do the job has been an equalizer. “If my brother goes down in the fire and I’m next to him, I got to get him out as my job. So, I must be able to lift 180, 200 pounds,” she says. “It doesn’t matter if I’m a woman. I’m a firefighter, and the women I work with are rock stars.”

Jusu was among 11 firefighters sworn in on January 15, 2021, by the Trenton Fire Department. In her first year on the job for Engine Co. 3, Jusu says one day stands out as the most difficult, one that had nothing to do with fighting fires. It started with an emergency call—someone was having trouble breathing, and it looked like there were drugs involved. “We stepped inside the house, and Grandma is crying in the kitchen. We went upstairs and Grandpa is doing the best CPR he can on a man. We took over and my captain and I took turns doing CPR on this guy for about 50 minutes. He was still warm, so we didn’t stop. But then finally, he went cold. The minute the medic called it and the cops went downstairs to let the family know, you just heard Grandma wailing. That’s hard, man.”

As hard as those days are, the deadly fire in the Fairmont neighborhood of Philadelphia in January was a reminder of just how important—and how painful—the job of fighting fires can be. In that fire, 12 people died including nine children when a Christmas tree was ignited by a lighter. “That was heartbreaking. No smoke detectors were working. One of the main things that the captain and director and everyone else are really focused on is how we as firefighters can be more vocal about fire prevention. That shouldn’t have happened in Philly,” Jusu says. “We need to be doing more surveys in the apartment buildings, making sure there are working smoke detectors, carbon monoxide detectors, that things are up to date as much as we can as a fire department.”

While the act of putting out fires is dangerous and taxing on the body, Jusu knows her job as a firefighter goes well beyond extinguishing flames and getting people to safety. “I lost my home to a fire, and it rocked my world,” she says. “I’m born and raised here in Trenton, so I know as well as anybody that we are not just putting out fires. We’re answering EMS calls. We’re seeing these people first, right when their worst nightmares are happening. We are at the end of that first call. And I feel blessed to do it.”