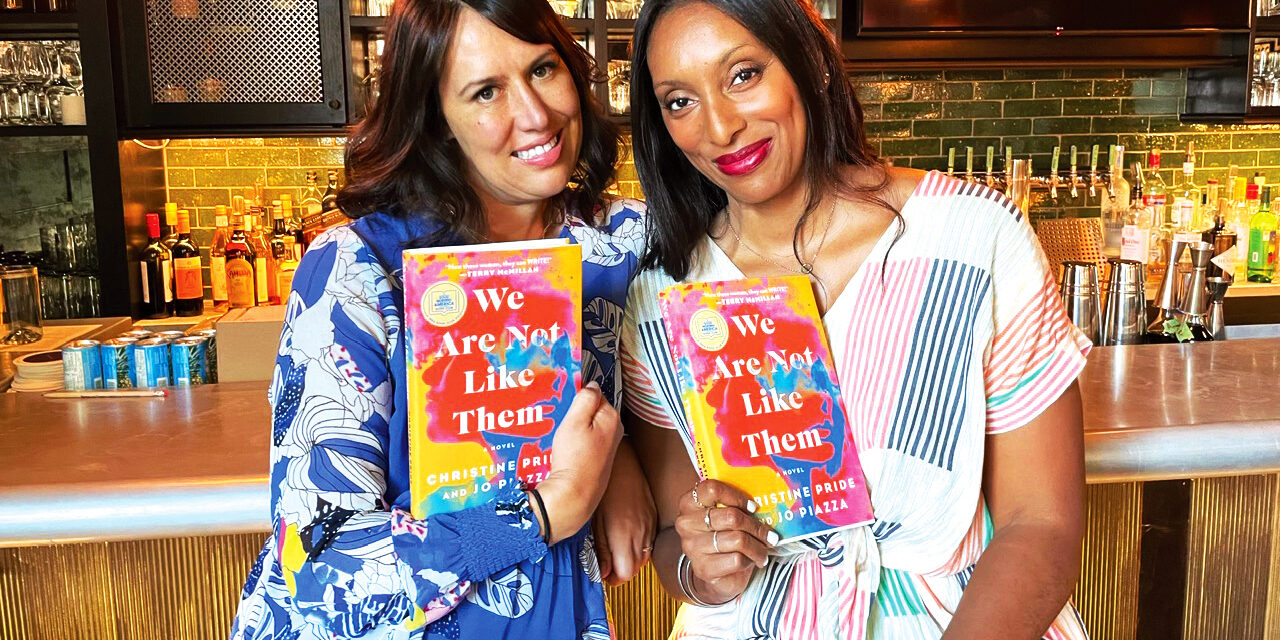

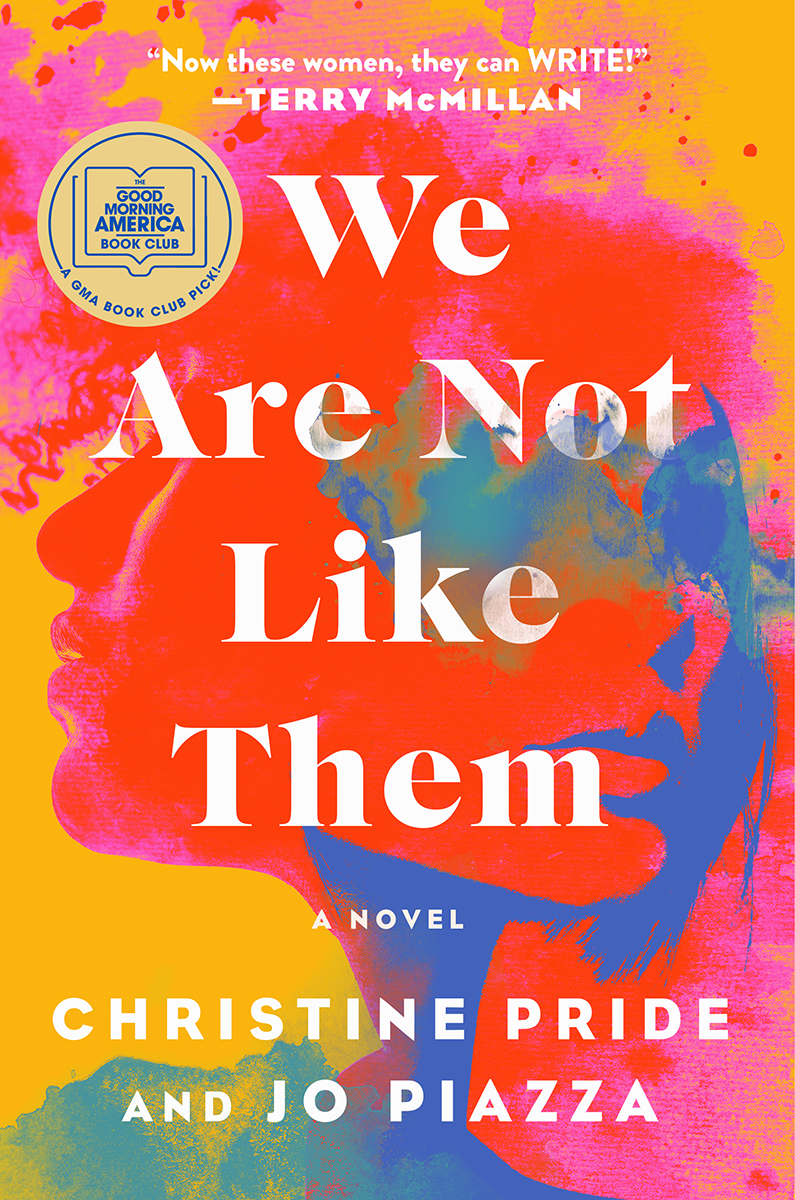

In their book, We Are Not Like Them, set in Philadelphia, Christine Pride and Jo Piazza tell the story of an interracial friendship tested by a police shooting that hits too close to home. In real life, the arduous writing process of such a challenging topic brought their own friendship to the brink.

In 2017, Christine Pride was feeling haunted by the rash of police shootings in post-Ferguson America, 3 years after 18-year-old Michael Brown was shot and killed. Pride was a book editor at Simon & Schuster at the time, and she had an idea for a story that she was burning to tell. “The idea was to write about what would happen to an interracial friendship between a Black woman and a white woman when the white woman’s husband was involved in a shooting of a Black youth,” Pride says. “How would that impact their friendship? What would happen in the aftermath between these two women?”

Around that time, Pride and Philly-based journalist Jo Piazza had just finished a successful collaboration with Pride editing Piazza’s latest book, Charlotte Walsh Likes to Win. Feeling like their writing styles were compatible and their friendship was sturdy, in January of 2018 Pride “proposed,” or at least that’s what Piazza likes to call it. “When [Pride] approached me with this idea, I just got the chills,” Piazza says.

“I felt like this book had to be written. I’ve been a journalist my entire adult life, but as I’m seeing all these shootings and violence against Black men and women, I knew that the media was not doing any of these stories justice. They were not conveying the humanity of anyone involved.”

And so, in 2018, they set about collaborating on a book that would change both their lives.

A Novel Idea

Although there are plenty of exceptional nonfiction books that tackle issues of race, Pride and Piazza agreed there was an opportunity to fill a gap in the fiction market. “Fiction is such a beautiful way of showing other people’s lives, whether that is in regard to race, class, or geography,” Piazza says. “It’s such a great way to fully understand another human being.”

The idea was to collaborate in writing a novel, which would be told from the alternating perspectives of Riley and Jen, two women who were born and raised in Philadelphia. As events unfold, they are forced to confront the realities of systemic racism as well as their own personal unconscious biases.

However, Pride and Piazza soon discovered the terrain was much more treacherous than it looked from the outset. Even the logistical challenges they encountered proved difficult—everything from their 3-hour time difference to whether to use Google Docs for collaborative editing seemed to slow them down. “We quickly realized that when we encountered creative differences, we didn’t have a plan for who was going to arbitrate and how we would work them out. I liken it to a marriage because we had to learn to communicate in so many different ways and on different levels. We had to learn to communicate as writing partners and as two creatives coming together,” Piazza says. “And then we had to talk about race on top of all of that. It was a process to work through all of those issues and sort them out mentally, emotionally, and logistically.”

Early in the writing process, Piazza told Pride that she often avoided talking about race, afraid that she might sound stupid or ignorant or simply say the wrong thing. But Pride pushed back on that sentiment, saying that Black people don’t have the luxury of avoiding the topic. With some of the fundamental issues of race causing conflict, there were many moments when it felt like they wouldn’t make it to the finish line, Pride says.

In the end, it came down to hard work and the willingness to believe in their story and in each other, Piazza says. “We had to have hard conversations,” she recalls. “It came down to trusting and respecting the other one to know that we were both doing what was right for the book.”

You’re never going to have one conversation and reach a racial utopia. If this is a muscle you develop over time in terms of talking about race, then we have to prepare for it to be a journey.

Talk Amongst Yourselves

Having conversations about race, especially with people from other races, can be challenging. Here’s what Pride and Piazza learned along the way.

Be patient with yourself and others.

“This is a process; it’s ongoing,” Pride says. “You’re never going to have one conversation with somebody and reach some racial utopia, a kumbaya moment. If this is a muscle that you develop over time in terms of talking about race and being open to this, then we have to prepare for it to be a journey.”

Stay open to possibilities.

“It’s about having some awareness of what our expectations are and leaving them at the door so there is space for something completely different to happen,” Piazza explains.

Face your fears of saying the wrong thing.

“It’s a real thing to be afraid of the other person’s reaction, but if we don’t face that fear, we can never have these important and meaningful conversations,” says Pride.

Give others grace.

“Let’s not be so quick to write people off,” says Pride. “There’s a line, of course—you are not going to have a bigoted friend or turn a blind eye—but you also can’t be so quick to make judgements about people or to be reactive if they say or do the wrong thing.”

Don’t shy away from uncomfortable conversations.

“Try to dig into it because those are the places where you actually start to shift your perspectives, where you actually feel growth and where your friendship also gets stronger,” Piazza says.

We are Not Like Them

Their novel begins in the voice of 14-year-old Justin Dwyer, a Black youth from Philadelphia who has just been shot by two white police officers. We soon learn that two officers who were involved in the shooting had mistaken the boy for a suspect of an armed robbery and thought he was reaching for a gun instead of the phone he was fishing out of his pocket.

This shooting is the event that sends the two friends reeling. Jen, who we learn is white and pregnant with her first child, is married to one of the officers who shot Justin Dwyer. Her best friend, Riley, a Black woman, is one of the broadcast journalists covering the story. As the story unfolds, we learn that these two women have been best friends since kindergarten, although they’ve never confronted the issue of race head-on with each other. As race becomes the central issue, the driving question of the book quickly turns to how this friendship can remain intact.

Jen struggles to support her husband while also recognizing the role he played in taking the life of a teenage boy. She also confronts her own blind spots when it comes to race. Early in the book, she actually tells a group of reporters, “My best friend is Black,” as if to wave away her own unconscious (and sometimes conscious) biases. Throughout the book, as the friendship becomes increasingly strained, Jen is forced to look in the mirror and consider how others might interpret her actions.

While the authors do not assign blame to either character, they do shine light on ways that each character could have been more honest or supportive. “In the book, Jen thinks she’s a really good friend to Riley. In a lot of ways, she is, but on the topic of race, she is falling short,” Piazza says. “We want readers to root for the characters to talk, just have it out and speak their minds and be honest and open.”

For her part, Riley recognizes where avoiding the topic of race with her best friend has been a contributing factor to leading them to this moment of uncertainty in their friendship. Pride says she deeply related to Riley’s plight. “As a Black person who exists in a lot of all-white spaces, you tend to wear a lot of costumes. It’s like you’re wearing an identity to some degree, and that’s hard to shake off at will,” Pride explains. “You get to a point where you’ve spent so much time being this other person that it’s not so easy to suddenly become ‘your real self.’ That dissonance is something that Riley struggles with.”

Stranger Than Fiction

Pride and Piazza started writing We Are Not Like Them in the fall of 2018, shortly after a rash of police shootings that year, including Stephon Clark, Antwon Rose, and Emantic Fitzgerald Bradford Jr., and they were virtually finished writing when George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, 2020.

As the Black Lives Matter movement gained momentum throughout the summer of 2020, the authors continued to revise the book. By the time Chauvin was convicted and sentenced to more than 22 years in prison, We Are Not Like Them was nearing publication. All those events made the book feel even more meaningful for Pride and Piazza. As society continues to grapple with the issues around racial equity and justice, the hope is that the novel will encourage people to ask hard questions of themselves and consider what is possible. “We want people to read this book and think about what justice can look like in these instances from everyone’s point of view,” Piazza says. “It’s something different to a mother; it’s something different to the community; it’s something different to the police force. Everyone has a different point of view on this, and that’s another thing that we want people to discuss and dig in to.”

Unlike many other books in which there are clear heroes and villains and there’s a strong perspective on who is to blame, the characters in We Are Not Like Them are nuanced and leave plenty of room for reader interpretation, which Pride says is more relatable to a lot of people. “You can agree or disagree with our characters. That was part of our intentionality of not going into it with an agenda,” she says. “We want to have that moment of feeling and realization and honesty, because that’s the moment where people start to think differently.”

Whatever perspectives the readers come away with, both Pride and Piazza say they hope the book inspires open dialogue and self-reflection, much like it did for the authors themselves throughout the process of writing the book. “I think I’m a better friend to [Pride] now. I definitely see the world in a different way [than I did before writing this book]. I have developed new muscles in having conversations,” Piazza says. “I’ve been very humbled by this writing process and by writing this book. And I’m so excited to see the conversations that it’s continuing to spark.”