Cycling saved Linette Messina’s spirit at several points in her life. Here, the Real Woman photographer shares her journey to finding her way, one ride at a time.

When Linette Messina was growing up in West Chester Borough, PA, she was always riding her bike. It got her from here to there, but it also took her away from the painful domestic-violence situation that was often seizing control of her home. “We used to run away from home a lot,” she says. And so, nearly 30 years later, when her marriage began to fracture and her home life felt stifling, she turned to her bike again for a way out.

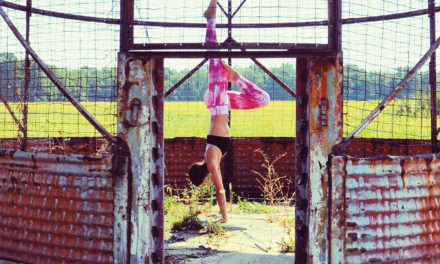

Messina, a Philadelphia-based photographer, had remained active throughout her adult life, mainly doing CrossFit. But in the height of the pandemic when everything was shut down, Messina dug out her old road bike—the one she rode to the bars and classes in college at Drexel University in Philly. “The tires were flat, and it was pretty rotted out. I took it to a shop for a tune-up, and when I finally got it back, I went out riding in the city. It was so good to be out in the world on my bike, and I felt like I was 20 again. I remember my husband at the time took a picture of me giving the devil horns with the bike,” she says. “He had no idea he was documenting my escape.”

The Wheel Deal

At that point in her life, the 46-year-old photographer was raising her two sons with her husband, and she felt unwanted and unappreciated. She was deeply unhappy and felt misunderstood, and riding her bike quickly became a way to clear her head and take time for her. On the bike, she felt freer and more herself than just about anywhere else in her life. “But that bike was a death trap. It was an aggressive road bike that my 40-something body wasn’t accustomed to anymore, and I got into a wreck, and pedaled home with a bloody calf,” she recalls. “So, I called my buddy, Fernando, who is a bike mechanic, and asked him what to get. I asked him what those bikes were called where people could ride on dirt or the road, and he told me to get a gravel bike.”

Gravel bikes offer riders more versatility—they have less suspension than mountain bikes, making them faster than mountain bikes on paved roads. They also have a sturdier frame than road bikes, so they give riders more stability on dirt roads or unpaved paths. Messina started riding her new gravel bike mainly on the Schuylkill River Trail (SRT), a multi-use path that extends 120 miles and includes Forbidden Drive in Wissahickon Valley Park, a dirt path that’s closed to car traffic.

While she found places to ride, Messina also quickly discovered a welcoming and diverse local cycling community. When the killing of George Floyd by police officers in Minnesota inspired more conversations about racial inequity across the country, Messina realized she was facing an identity crisis at home. As the daughter of a Sicilian father and a Puerto Rican mother, Messina considered herself a woman of color. “I was very sensitive to racial issues, and with all the difficult conversations happening about race, it’s something I wanted to bring up at home with the kids,” she says. “But at home I was being told that I wasn’t a woman of color, that I was white, and that was just really hard to grapple with.”

She discovered Kings Rule Together/Queens Rule Together (KRT/QRT), a community of cyclists of all ages, genders, skill levels, and races. “I got to meet so many people of color and just a different mix of folks than I was used to hanging with. I started riding with them weekly,” she says. “That’s when I went to Vermont for a women’s gravel clinic, and I met all these amazing women, many of whom were amateurs or beginners learning how to ride on gravel.”

I felt like if I can ride 60 miles on this bike and actually finish this ride, then I can leave a shitty marriage. The cycling community helped me find the courage to start living for me.

Beginner's Advice

Interested in taking on gravel riding? Before you buy a bike or equipment, Messina recommends checking out Radical Adventure Riders (RAR), which has chapters throughout the United States. “RAR offers amazing resources for getting started. You can figure out what bike to get. They have workshops,” she says. “Before buying, you can utilize their bike equipment library so you can try out different gear because it can get expensive.”

Check out radicaladventureriders.com for more information.

Slow Ride

Messina’s first big gravel race was called Rooted Vermont, an event that ran for 3 years before going on an indefinite pause. Then in 2022, she signed up for the Last Best Ride, an annual gravel race in Whitefish, MT.

On her way out to Montana, her father passed away. “I was dealing with so much grief in my heart throughout that ride, but the bike helped me through it,” she says. “I felt like, if I can ride 60 miles on this bike and actually finish this ride, then I can leave a shitty marriage,” she says.

That journey to Montana was a life-changing one in so many ways. “The cycling community helped me find the courage to start living for me,” she explains.

While going through a separation (on the way to divorce) was painful, Messina found a renewed sense of self. Her passion for gravel races continued to soar—she now owns two gravel bikes and one mountain bike—but Messina still rides her way. Unlike many riders who race the clock or aim to reach a personal best, she is riding for the experience, often stopping to take photos or take in the scenery. “I like to enjoy it. I like to stop and have a snack or two during the event. It’s a way for me to get out and travel, ride my bike in new places, and meet new people.”

Messina has big dreams and plans for rides she wants to do on her new bike—a Salsa Warbird. Top of the list is the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR), one of the most recognized off-road routes in North America, a 3,000-mile ride that starts in Banff, Canada and finishes at the U.S./Mexico border in Antelope Wells, NM. She also dreams of the Camino de Santiago, a network of pilgrimage trails that lead to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. Whatever paths she takes, she’s grateful to be part of the cycling community. “I think cycling brings out such diverse and interesting people because you can be any shape or size or religion or sexual orientation to ride a bike, and I love that about it.”