For many of us, the suicide of 55-year-old fashion designer Kate Spade, likely influenced by years fighting severe depression in the dark, was a shocking reminder how overpowering and unrelenting mental disorders can be. Can we do better for people with depression, and can it ever be enough to save them?

Today, Maria Devon got out of bed. She pulled herself from the comforting warmth of her sheets, scooted to the edge of the mattress, and let her feet hit the floor with a thud. Then she stood and shuffled to the bathroom, intent on starting her day and facing her demons. She’d like to think this process will be easier tomorrow. But it may not be. It may never be.

Devon was an anxious child. Socially awkward. She lacked self-confidence. She didn’t want to go to school, and when she got mononucleosis at 14 years old, her emotional problems manifested as an eating disorder and body dysphoria. She was diagnosed with depression, making her one of 16 million sufferers in the United States, and her parents sent her to a mental institution for the summer. “I made the best of it. I made friends. I learned a lot about mental illness really early on,” says Devon (not her real name), now 42. “That was hard, and the stigma at school was weird. I didn’t want to go out. I didn’t date. I wasn’t ‘normal.’”

For the last 30 years, Devon has battled. She has scratched and punched and clawed her way, fighting tooth and nail to overcome—or at least outlast—depression. “The diagnosis changes constantly, and I’ve been on every medication at this point. It’s been 30 years of doing this, of feeling out of place,” she explains. “On a bad day, I can’t get out of bed at all. I can’t eat. I’m offering constant I’m sorries and feeling like I don’t belong. I basically developed two personalities. When I am working, I have my face I put on for work, and then I fall apart at home.”

Over the years, Devon was prescribed just about every cocktail of medications for depression, from Prozac to Zoloft, with limited improvement. She spent time in mental institutions. She underwent shock treatment—16 bilateral shocks—which she says radically changed her forever. And she’s been in therapy for decades. Each intervention had limited benefit to her mental state.

In 2013, after her older sister, whom she adored, died suddenly at 42, leaving her husband and two kids behind, her grief became a catalyst that further deepened her depression. “When my sister passed away, I started drinking heavily. I’ve been sober for over a year now, but I was in a really dark place,” Devon says. “Depression causes you to go places you wouldn’t normally go, even to contemplate killing yourself.”

And in September 2013, Devon tried to take her life. She was at her parent’s house, and a fight with a family member triggered unrelenting waves of suicidal thoughts. She felt like a burden to the people who loved her, and she was consumed by the suffocating feeling that she could never escape the depression that had plagued her for so long. “I felt like no one understood, and I couldn’t live like that anymore. I felt worthless. I felt trapped in a life and in my own mind with obsessive thoughts,” Devon recalls.

So she swallowed two jumbo-sized bottles of Tylenol and waited for the drugs to end her life. But either because she was disoriented or because some part of her did not want to die, Devon went downstairs and told her parents what she’d done, and they were able to take her to the hospital in time to save her life. “I sat in the hospital, possibly facing a liver transplant, and all I could think was What now?” Devon says.

Fashion designer and icon Kate Spade took her life on June 5 at age 55.

Depression is a horrible affliction. It’s something you can’t see and you can’t measure, so you can’t know their pain.

Ali O’Grady is the founder of Thoughtful Human, a plantable card company designed to help people find honest ways to communicate in dynamic relationships and challenging circumstances.

These were difficult years when I struggled with depression. The struggle was intense. I could analyze the source of my depression forever. Low self-esteem might be rooted in childhood feelings of inferiority. It could relate to failing to meet impossibly high standards. And of course, there are always the societal issues of racism and sexism. Put it all together, and depression is a tenacious and scary condition.

When Darkness Falls

If you were like most of us and didn’t have a vantage point beyond the brightly colored handbags and accessories in the SoHo storefronts, Kate Spade’s suicide in June came as a complete surprise. Her brand, which she started in her apartment, was known for being colorful, accessible, affordable, and with something aimed for women ranging in ages and backgrounds. How then, could such a successful, prominent, talented woman be found dead in her Park Avenue apartment, hanging from a red scarf on a bedroom door, leaving behind a 13-year-old daughter? Her husband, Andy Spade, said in a statement that his wife suffered from depression and anxiety for many years. However, he also explained that there was “no indication and no warning that she would [take her own life]. It was a complete shock.”

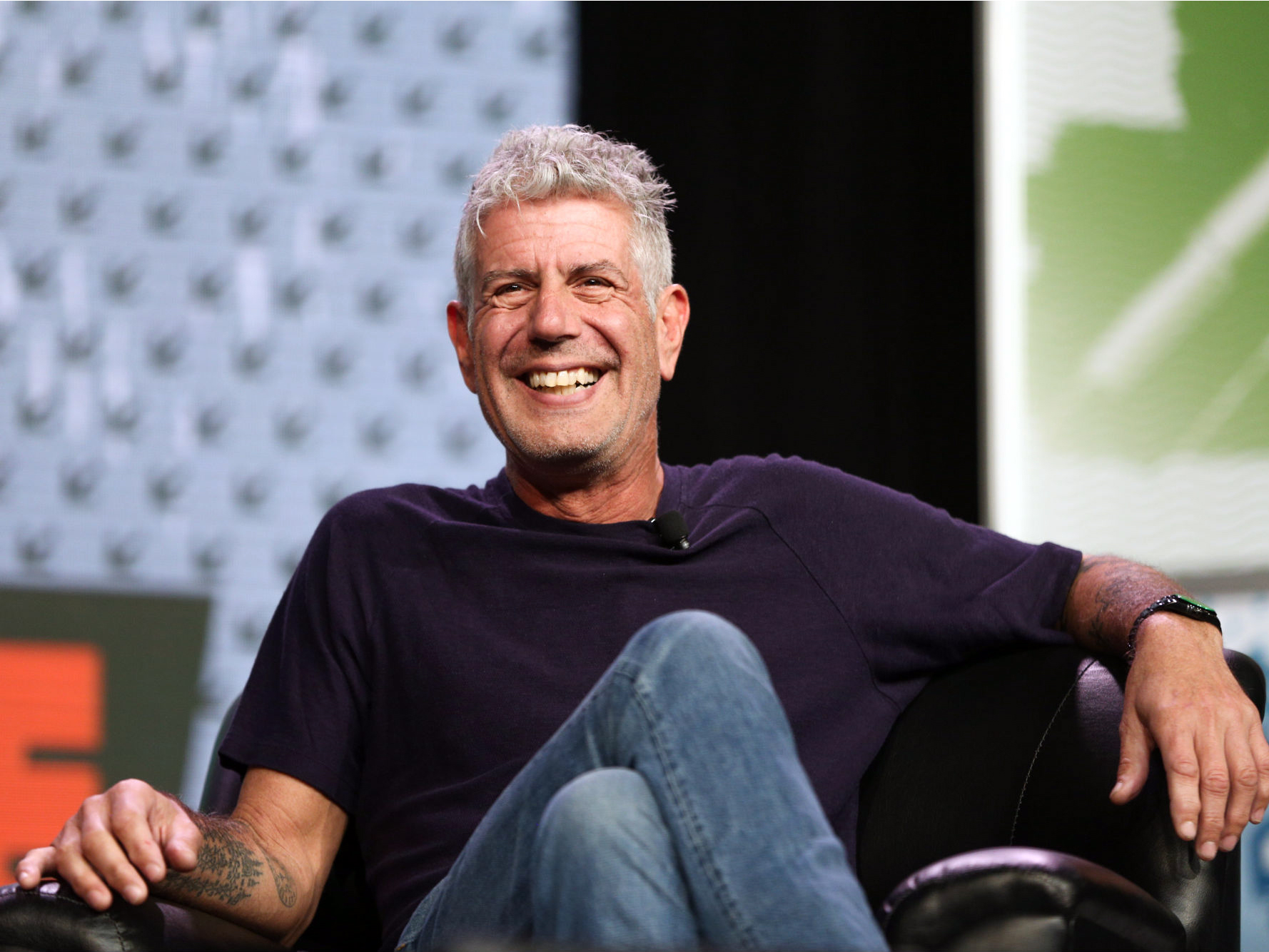

Before the American public could catch its collective breath from the blow, chef and food icon Anthony Bourdain took his life in Kaysersberg, France, also having hung himself and also leaving behind a daughter, 11-year-old Ariane. As we scrolled through our Facebook and Twitter feeds, it seemed like everyone was asking themselves the same question at once. How could this happen?

The answer is unknowable since none of us live in the minds of Kate Spade or Anthony Bourdain. However, the daily battle to maintain an upbeat façade can take a huge toll, says Ali O’Grady, founder of Thoughtful Human, a plantable card company based in Oakland, Calif., designed to create open dialogue around challenging life circumstances and relationships (depression, grief, addiction, illness). She started the company, which now sells card series online and in retail, after her dad lost a 10-year battle to colon cancer, and she found that people didn’t know how to help her through her grief. “I am never surprised by celebrity suicides like Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain more so than everyday people. Depression doesn’t discriminate,” she says. “And then there’s this added layer of guilt for being depressed when you have money or other resources people envy. Similar to the guilt of being in bed and depressed on a nice, sunny day. But that’s not how it works, depression doesn’t care about your status or the weather.”

Lee Myer, a clinical social worker with a private practice in upstate New York says his experience with Mobile Mental Health, a crisis response program that offers immediate intervention to people having mental health crises by phone or face to face, has underscored that depression can lead to suicidal thoughts or attempts as a result of prolonged battles with the disease or very suddenly and unexpectedly. People’s neurochemistry can be hard-wired toward depression, he says.

From a biological standpoint, low levels of neurotransmitters may play a role in why some people are more susceptible to depression, including serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. “But depression is also something that can be learned or absorbed and incorporated,” Myer says. That’s where the risk factors come into a play, including illness, sleep disorders, gender (women are twice as likely than men to have depression), substance abuse, and major life changes like divorce, death of a loved one, or a job loss.

This was highlighted last month when singer Janet Jackson talked openly about her battle with depression in Esquire magazine, saying, “I could analyze the source of my depression forever. Low self-esteem might be rooted in childhood feelings of inferiority. It could relate to failing to meet impossibly high standards. And of course, there are always the societal issues of racism and sexism.”

Myer says this a particularly treacherous time for people suffering from depression, even from a societal standpoint. “One risk factor is that we live in a very stressful time. There’s a lot of fearful conditions that are worrying and surround us, whether it’s the environment or political strife or a rise in terrorism,” Myer says. “The fact that we live in the Age of Information, the fact that we can be communicating within the moment, means there’s the potential for inflaming situations. You are taking an ember and seeing it grow into a full out inferno.”

Anthony Bourdain, 61, the chef-turned-TV host was found dead in his hotel room in France where he was filming his hit CNN show, Parts Unknown.

What Can (and Can’t) We Do?

If you’re in the role of supporting a loved one who is suffering from depression, Fowler says she’s learned from helping her own daughter that less talking and more listening is the key. “You want to come from a place where you have no judgment and you just listen,” she says. “Be curious about what he or she is experiencing. People—especially adolescents—don’t ask for help when they feel judged.”

O’Grady echoes the sentiment and says consistent outreach and honest dialogue are sometimes enough to make a difference. “When you’re in crisis you can feel so isolated—you feel like you’re the only one in the world,” she says. “At the end of the day, nothing you’re going to say is going to “fix” things for someone in crisis, but you can keep showing up and asking the questions.”

As the friend or family member, it’s also crucial to remember that we can’t single-handedly save anyone from their pain or suffering, no matter how much we want to. “We can’t make pain disappear or give someone else the will to live. But there’s a place where you can help them get into a more serene place,” Myer says. “Try to take the tact that you’re going to make sure this person knows you love them, and be as available as possible, but still give your life the attention it needs and know that you can’t necessarily help this person from being in pain or attempting or completing suicide.”

Since every individual has difference neurochemistry and life circumstances, there is no one-size-fits-all answer for coping with depression. However, the industries and communities offering support for depression are growing. “Working with people who are profoundly depressed and suffering for many years, I’ve found there’s been a growing creative process to recognizing there are so many different approaches to well-being,” Myer explains. “People have gone beyond medications—there’s more attention to mindfulness, for example. There’s a range of different treatment approaches and life practices that can potentially be employed.”

Devon says at this point she’s very focused on dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), a cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy that helps a person identify their strengths and builds on them so that the person can feel better about him/herself and their life. But with everything she’s tried over the years, the best advice she can offer people battling to keep their heads above water is to exercise self-compassion. “Be kind to yourself. If you can get outside of yourself, that’s the key. Get outside of your own darkness,” she says. “Get a pink bike. Try thrifting. Take pleasure in simple joys. Take your medicine. Go to your doctor appointments. That’s your job. The way to transform is that you really have to push.

“You have to fight every single day.”

Causes of Clinical Depression

Many things contribute to clinical depression. For some people, a number of factors seem to be involved, while for others a single factor can cause the illness. But remember that oftentimes people become depressed for no apparent reason.

Biological

People with depression may have too little or too much of certain brain chemicals, called neurotransmitters. Changes in these brain chemicals may cause or contribute to depression.

Cognitive

People with negative thinking patterns and low self-esteem are more likely to develop clinical depression.

Gender

More women experience depression than men. While the reasons for this are still unclear, they may include the hormonal changes women go through during menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth, and menopause. Other reasons may include the stress caused by the multiple responsibilities that women have.

Co-occurrence

Depression is more likely to occur along with certain illnesses, such as heart disease, cancer, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, Multiple Sclerosis and hormonal disorders.

Medications

Side effects of some medications can bring about depression.

Genetic

A family history of depression increases the risk for developing the illness. Some studies also suggest that a combination of genes and environmental factors work together to increase risk.

Situational

Difficult life events, including divorce, financial problems or the death of a loved one can contribute to depression.

—Source, Mental Health America