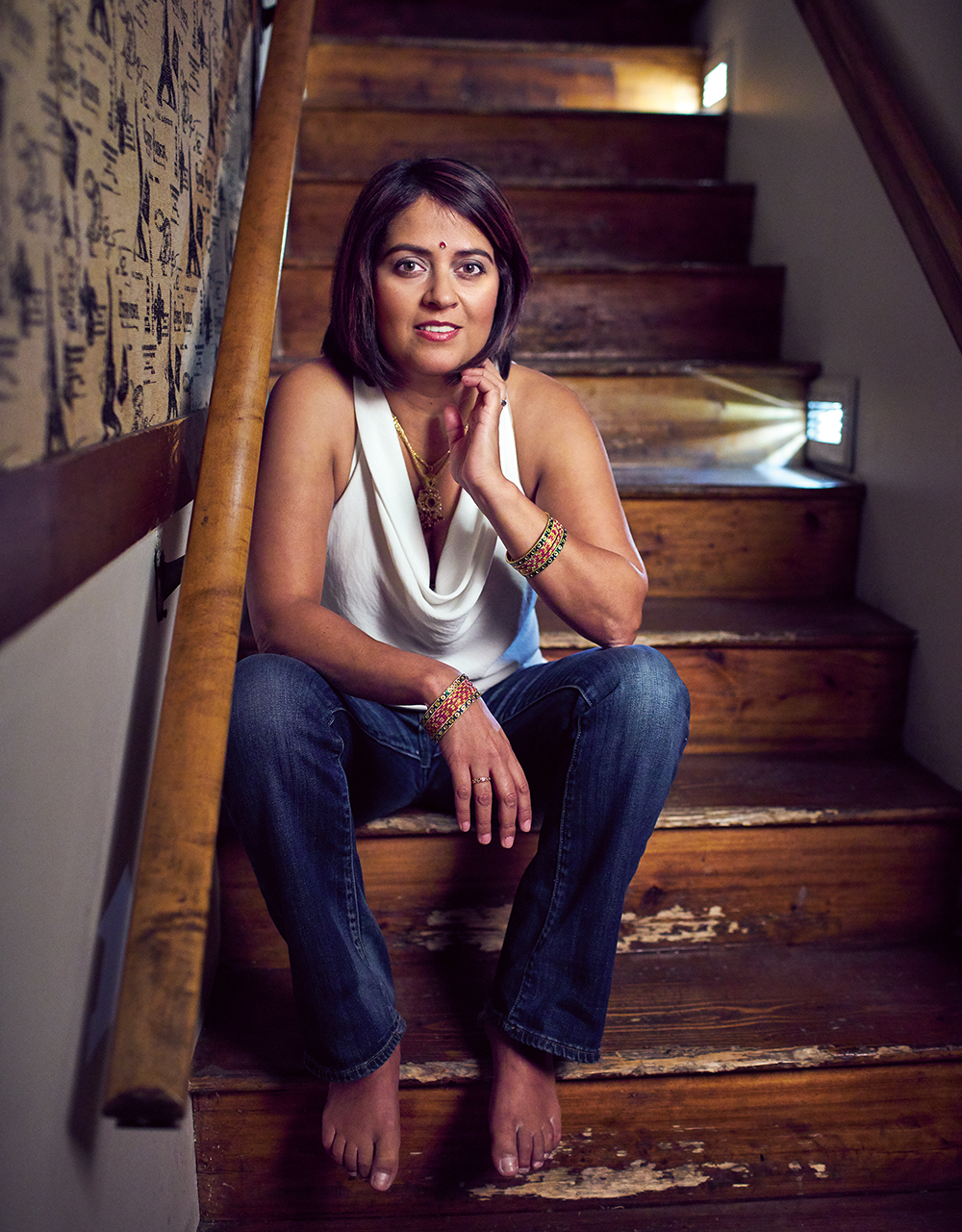

After decades struggling to overcome her uniqueness, this 45-year-old woman is embracing it, including her Indian heritage and being out as a gay woman. And she’s never been happier.

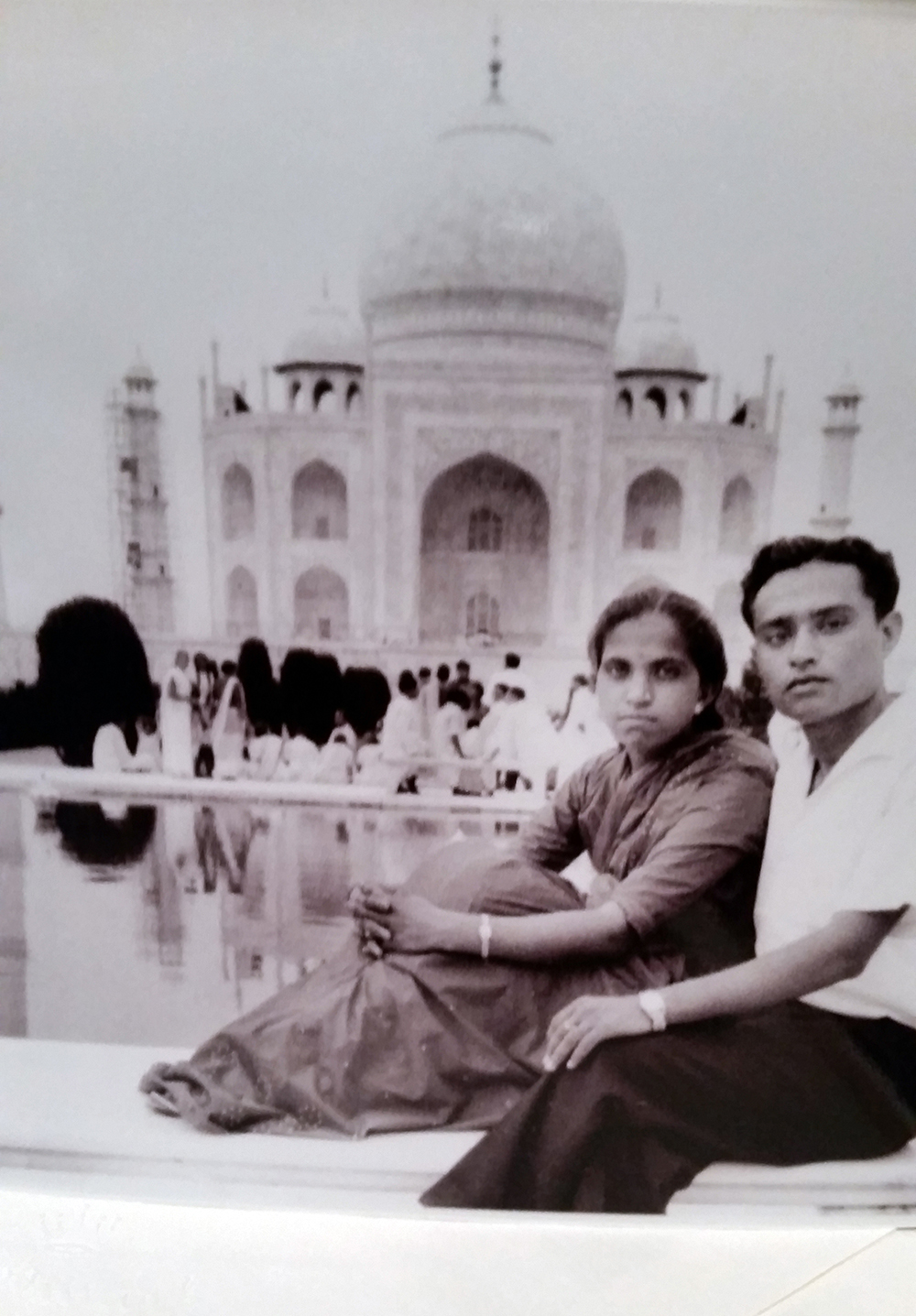

On her first trip to India last fall, Amita Mehta showed her tour guide an important picture. Taken in front of the Taj Mahal six decades earlier, 16 years before she and her twin brother were born in Kampala, Uganda, it shows her Indian-born parents gazing at the camera—baby-faced, intent, and unaware of the upheaval they will face in Uganda at the hands of Idi Amin Dada. In the photograph, they have no idea they will lose all their worldly possessions, their home, and their financial security alongside hundreds of thousands of other Asians whom Amin abruptly and ruthlessly expelled in 1972. They don’t know they will become refugees. And they have no inkling that they will face poverty and struggle to rebuild their lives and overcome cultural challenges and language barriers in the United States.

Last fall in India, Mehta had the chance to reflect on the tumult her family endured, but also their strength of spirit. With help from her guide, she returned to the exact spot where her parents had sat and smiled for a picture. But the smile isn’t Mehta’s trademark buoyant (and somewhat mischievous) grin; Instead, you can see the weight of the moment taking its toll.

“The guide told me to close my eyes as we approached the entrance, and when he told me to open them, the white marble of the Taj Mahal was glowing right in front of me. It was emotional,” Mehta says. “It suddenly felt like every sacrifice [my parents] made was worth it, and I was representing them.”

The moment was heavy with significance, and not only because she had the chance to visit her family’s birth roots for the first time. She could celebrate her career success—despite having started her life in poverty and powering herself through college, Mehta was now a vice president at Prudential Financial. But perhaps most significant of all, on that October day in front of the Taj Mahal, Mehta was also a newlywed. She had married the love of her life, Kristen Kemp, just a few months before her India trip. She was living as an openly-gay, married woman, after suffocating in the closet for many years.

As she sat in front of the monument, she reflected on her life and how it had somehow come together, against pretty long odds. To get there, she had to stare down poverty, cultural differences, and eventually the realization that she was gay, which she feared would put her at odds with her parents and the traditions of her heritage. But there she was, with the wind at her back and a life of possibilities awaiting her.

The Salvation Army took us in, and I thought I was going to be taken away from my family. I think that’s when I first felt that we were nothing—had nothing. We were reunited, but things were hard, especially for my parents.

I wish I could tell my younger self to own who you are and don’t try to live up to expectations set by others. The people who matter will love you unconditionally and respect your strength.

Coming to America

Mehta’s life began inauspiciously in Uganda, at the height of Idi Amin’s power, during the expulsion of all Asian citizens in 1972. She and her twin brother were born just weeks before her family was forced to leave the country, with nothing but the clothes on their backs. For Mehta’s father, Prabhashanker, this wasn’t the first time he’d lost everything—he’d been orphaned at 6 years old after his mother died giving birth to his sister and his father committed suicide out of grief. But he became top of his class at a school for orphans, which was founded by Mehta’s maternal grandfather, and he was to be offered the chance of a lifetime—to meet his future wife, Bhanumati, and make a life in Kampala. And he did. In fact, the Mehta family had financial security and societal standing before they were forced to leave.

“My dad took his brand-new Toyota Corolla into town and gave the keys to a homeless man, and we left with $140,” Mehta says. “Then we were separated. Dad was stateless, so he was sent to a camp in Italy, and the four of us kids went to a refugee camp in England with Mom.”

A Lutheran church agency helped the Mehtas reunite and emigrate to the United States. And so, on a snowy winter day in 1973, the entire family landed at JFK Airport, Mehta’s mom in just a sari and sandals, before traveling to Lancaster County, Pa., to stay with an Amish family until they could find a place to live. For a short time, the family of six lived in a dilapidated farmhouse before moving into a trailer where they would spend the next several years. Mehta’s father went from a career with Barclays Bank to a job as a day laborer in a chicken-processing factory, while her mom had difficulty finding work due to chronic, debilitating foot problems that seemed to come from being stung by a scorpion as a child. She required several surgeries just to walk without discomfort. While Bhanumati was in the hospital, church parishioners took Mehta and her twin brother into their homes.

Off and Running

As Mehta grew older, she learned to hide the economic and cultural differences that made her stand out from her friends. Despite the fact that Mehta was the only girl in her family, she was raised with the same expectations and household duties as her brothers, a departure from traditional Indian culture. Her dad signed her up with the Columbia Boys Basketball Association, and she thrived. She was smart and athletic, and became the point guard for her high school team. “I’d be at basketball practice, and people could smell curry,” Mehta recalls. She loved the family’s regular Wednesday pizza night because she didn’t smell like curry on the basketball court: “I remember saying, ‘Mom, if you’re coming to a game, can you not wear a sari? Can you wear pants or something?’ I regret that now.”

While Mehta had plenty of friends in high school and loved playing basketball, she also worked extra hard to get to college. As early as freshman year, she regularly visited the guidance counselor, gaining intimate knowledge of scholarship opportunities and financial aid. “I could have played Division I basketball on a full ride, but I didn’t want to leave my mom,” she says. “I knew I wasn’t going to play in the WNBA, and I didn’t want basketball to own me. So, I decided to major in business at Elizabethtown College, which wasn’t too far away. I filled out all the financial-aid applications by myself, and I maxed out loans and student aid.”

Mehta’s father had a heart attack just as she was moving into her dorm. Although he was OK, the family stress and the weight of her financial responsibilities cast a cloud over her college experience. She never felt like she quite fit in.

After college, Mehta climbed the financial-services ladder. From the outside, it looked like Mehta’s life was everything she could have ever wanted. But inside, Mehta was lost and confused. Then, at 30, something happened that rocked Mehta completely off her axis—she fell for a woman. “When we kissed for the first time, it was like, whoa,” she says. “It wasn’t like anything I’d felt before.” That was when things finally began to click into place.

Mehta knew her parents expected her to marry an Indian man, and, having never been exposed to gay people, she had no idea how to move forward. As she tentatively explored the gay/lesbian scene in Wilmington, she hid it from her family. “I started to withdraw—I was living a double life,” Mehta recalls. “I put on a happy face at work, but then I would cry behind closed doors. I was embarrassed and consumed by fear. I felt like I was letting my family’s sacrifices and my culture down.” She worried about what her family and friends would think, and how coming out would possibly stifle her career growth.

“For years, I built up so much stress, and it was exhausting to continue living a lie,” Mehta says. She eventually came out to her twin brother, Anil, who was compassionate and open-minded and reassured her that she was still the same person whether she was gay or straight. He promised to keep her secret for as long as she wanted. That turned out to be 5 more years.

“I wish I could tell my younger self to own who you are and don’t try to live up to expectations set by others,” she says. “The people who matter will love you unconditionally and respect your strength.”