At age 38, as I prepared to walk down the aisle, I dreaded my father’s absence.

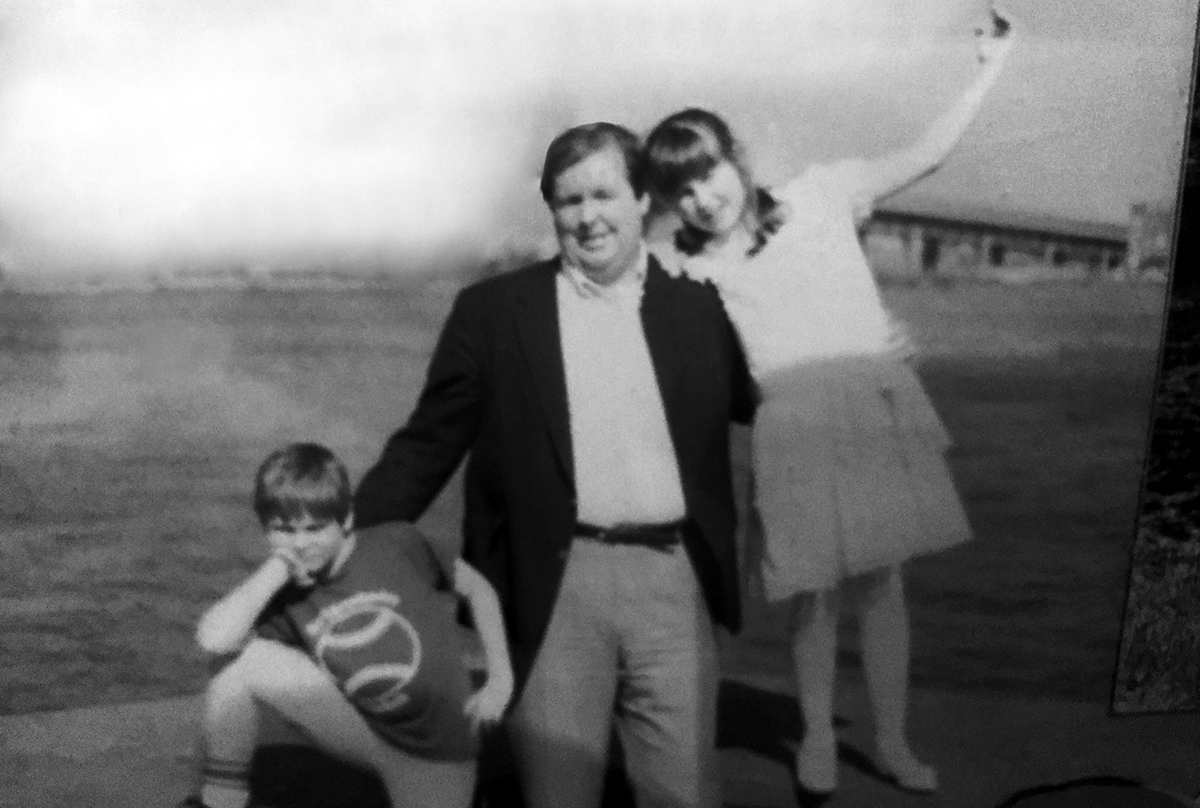

Mick Carney was killed when he was 54, when I was 25, by a teen driver on a phone who was lost. His life felt incomplete, our bond unresolved.

Now I was the one who was lost.

No amount of support alleviated my anger. A 17-year-old had taken away someone crucial, I thought, abruptly and with no consequence. I couldn’t live with the indignity, so I hid it. As a result, few things felt real and everything always felt urgent. As a young woman, I feared death around each corner. I tried to make an impact with my life, just in case. But preparing to die all the time had a drawback: I forgot how to live—a disservice to the man who’d taught me.

When we received our wedding photos, I noticed something strange: an empty spot on the stairs in our family picture, an extra seat at the tables during our reception.

Was my dad there?

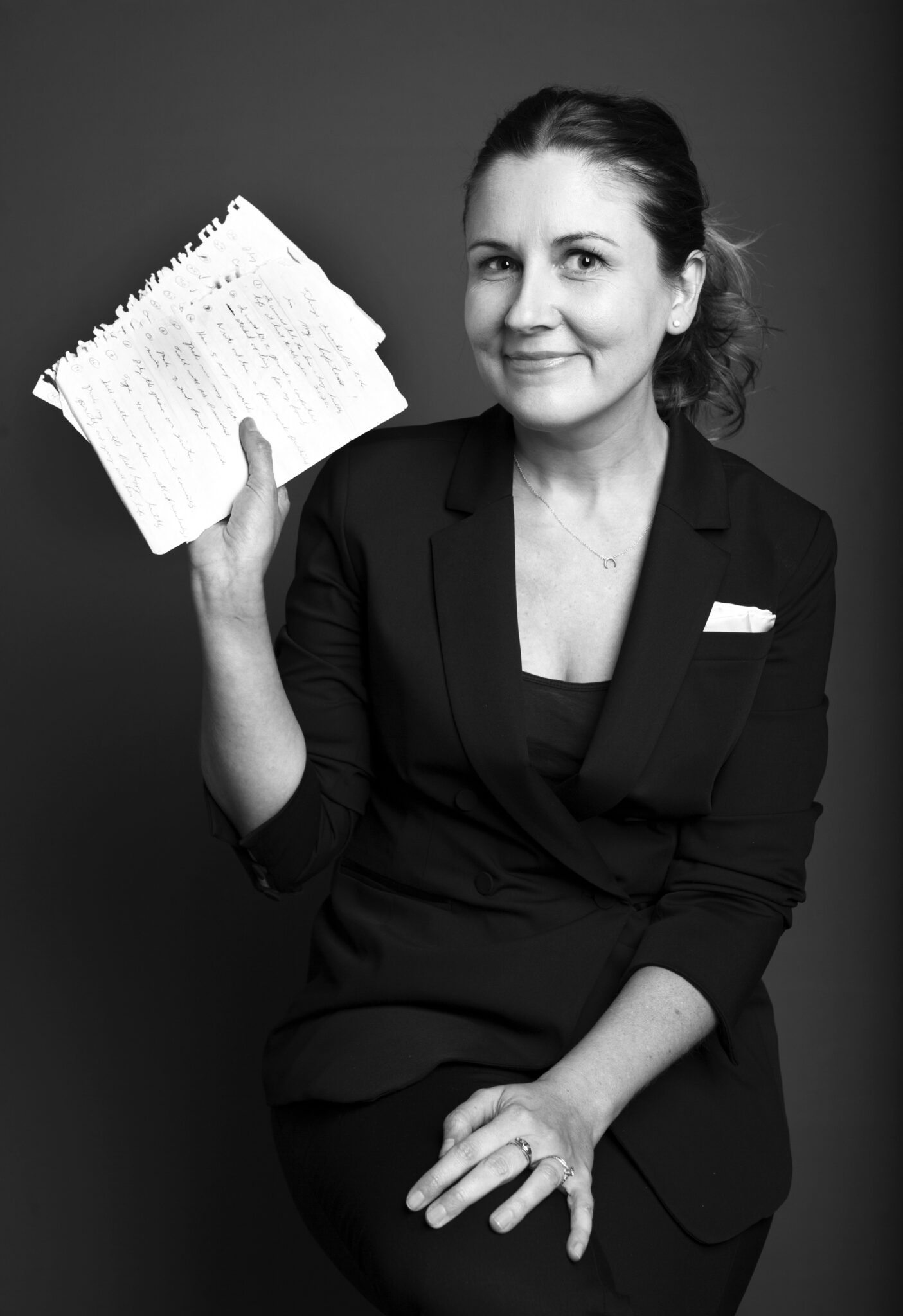

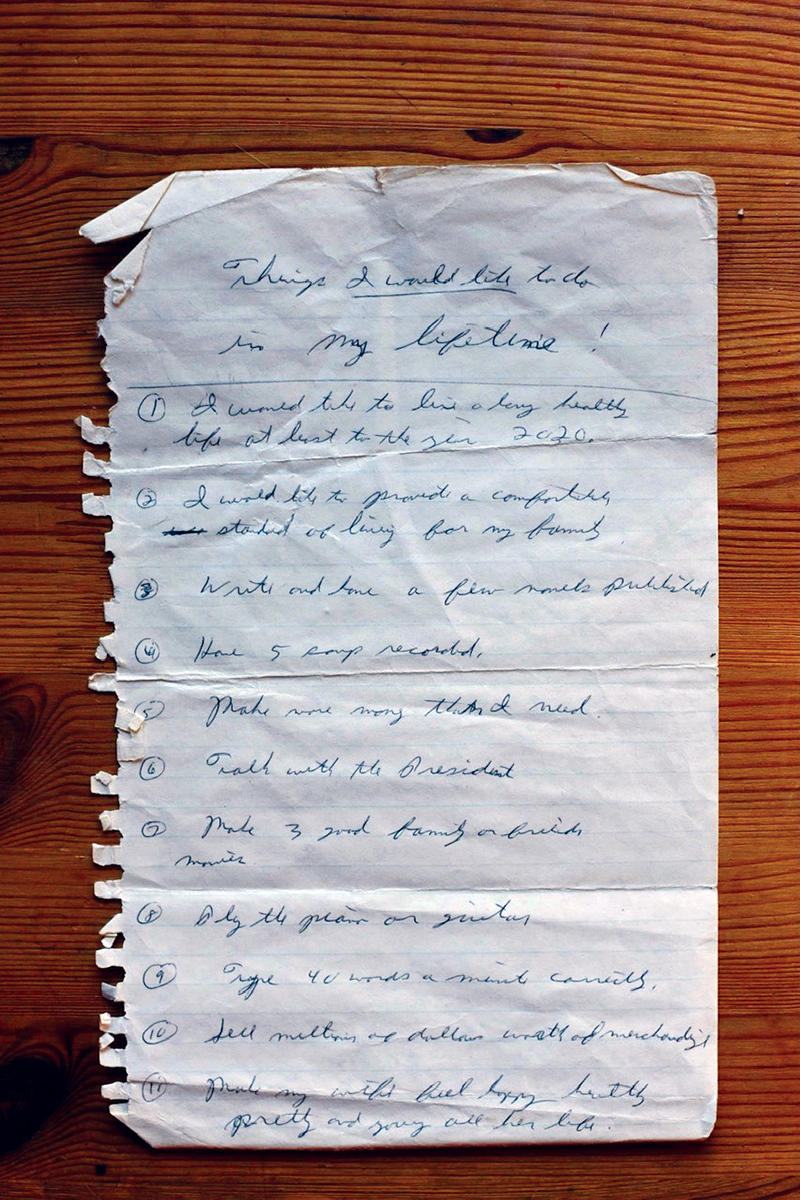

Six months later, my brother gave me a clue. During his move into his first house, Dave had discovered what appeared to be our father’s bucket list—which we never knew he had. Written in 1978, when he was 29, our dad had listed 60 things he hoped to do in his life. He kept checking it off, as evidenced by the different-colored pens. Dave remembered when he went to the World Series. We laughed at Dad’s almost indecipherable handwriting.

My husband, Steven, said out loud what I was thinking, “Laura, you have to finish this.” I saw my dad in my mind’s eye, smiling and nodding. I knew Steven was right.

I also knew that agreeing to this adventure at 38, newly wed and career-established, meant my life’s parameters might change. But I set forth anyway, on what would become a nearly six-year voyage.

The list was written by a man dreaming about his life, not preparing for his death. My dad was no longer with us, but his spirit still had a lot to teach me.

Here’s a short list of what I learned.

1.The only constant in life is change.

When I checked off “run 10 miles straight,” I peed my pants for 10 miles. When I jumped out of an airplane for “skydive at least once,” I puked on national TV. When I “rode a horse fast,” the only fast thing about the horse was how quickly he emptied his bowels.

Contrary to popular opinion, my first instinct wasn’t always right. With each list item, I had no idea how it would get done. So I adjusted. I stopped trying to control the agenda. Wanting to control things actually limits your life.

This is because when you control, you might stay on the path you want, but you might miss the path you needed.

2. Words matter.

Before I found the list, when it came to self-talk, I unconsciously repeated ideas about me that weren’t real, judgments implanted by someone else.

Because my dad’s bucket list was an unusual journey, it required that I let go of fitting in. Each list item replaced inner judgments about not being enough with proof that I was more than enough—for this particular pursuit. I trusted that my dad believed in me and wouldn’t let me fail, so soon

I believed in me too, and this led to rediscovering my faith.

When things seemed cruddy, I recognized there was a greater plan and maybe I was just experiencing the part where something not so fun happened. I prayed, “Thank you, God, for the abundance.” When I said it often enough, I began to believe it.

Choose your words carefully, as my dad often said. They tell the world who you are—and what you believe. They have the power to change what happens.

3. A little public humiliation is good for you.

After I’d peed, puked on TV, and ridden a pooping horse in public, I often joked, “What bodily function comes next?” I bled from scraped knees when I checked off “swim the width of a river.” The ocean pulled every limb at the same time when I wiped out before checking off “surf in the Pacific”

(I got it right on my 20th wave, during my second lesson). And when I checked off “own a $200 suit,” I got my period mid-triathlon, on my 40th mile of cycling, as four motorcycle cops rode on the hot Florida highway behind me.

We live in a society that mocks public failures, but they’re actually good for you. To check off my dad’s bucket list, I had to fail 54 times to succeed 54 times, often in public. The end result? Nothing embarrasses me.

I know who I am. What others think doesn’t matter.

My Father’s List: How Living My Dad’s Dreams Set Me Free, by Laura Carney, will be published by Post Hill Press on June 13, 2023, but can be preordered online now.

We become who we choose to be. That’s what my father taught me.

We are always co-creating our lives, but sometimes the universe needs a nudge. Declaring something out loud is like a prayer—it changes our behavior.

4. Pay attention to your intentions.

I decided when I was ready to write a book about my father’s list that I would donate half my author royalties to the causes of every person who helped me. Knowing this, and how the story might affect my friends who’d lost a loved one in a distracted driving crash, pushed me to keep going when I could not push myself. I also made two rules with my writing: always be kind and always tell the truth. As long as I stuck to those, I could write about whatever I wanted.

Oprah has said this many times, and I know now that it’s true—nobody with pure intentions can fail. The journey reflects why you started.

5. If you want to speak your mind, live by your beliefs.

Halfway through my mission I yelled at a family member for texting and driving. My husband reminded me that despite his educating me about the deleterious effects of factory farming, I still ate meat, a choice I made purely out of convenience.

I went vegan the next day. And vowed to complete an Ironman vegan—to demonstrate what living by one’s beliefs could do. I stopped lecturing about change and worked instead on being the change. I stopped shaming and started inspiring.

Being true to you is worth it, because it frees up your voice. Nobody hesitates to promote peace when they are at peace within.

6. What’s inner is outer.

I attended President Jimmy Carter’s Sunday school to check off “talk with the president,” where I learned that we’re always co-creating our lives—not with a parent, child, or spouse, but with God. Learning this gave me permission to pursue my dad’s list, write my book, and live my own life my way.

Goethe said we see in the world what we carry in our hearts. A person who gives kindness sees kindness. We are always radiating out what’s within.

7. Life is a gift, not a given.

I cringe when someone tells me I “lost my father,” because I know now that I lost nothing. My dad’s soul transitioned. Why should we, as human beings, believe that we get to decide when a soul transitions? My dad lived the life he was supposed to live, understanding that his life was a gift. And so is mine. After finishing my dad’s list, I no longer believe I am entitled to anything—list items worked out when I let go. When I recognized what a tremendous opportunity it is to be alive.

8. We move forward when we are ready.

I used to be a person who waited for my prince to come. I sat around wondering when fate would grant me that perfect job. This led to even more sitting around. One day I shouted, “I’m ready for that job now!” Soon after, I was hired. A few years later, I tried it again: “OK, universe, I’m ready to get married now.” And later, when checking off my dad’s list, I said, “I’m ready to write and publish my book now.” My dad courageously wrote down his life goals in one year, and I wrote my goals in the air.

We are always co-creating our lives, but sometimes the universe needs a nudge.Declaring something out loud is like a prayer—it changes our behavior. Once we decide we are ready, things move faster.

9. As long as you are giving, you are living.

I lost my job in Year Two of checking off my dad’s list, a career I’d worked hard on for 13 years. By Year Three, my bank account was empty. I also couldn’t walk anymore, let alone run (I’d been a marathon runner when we found the list). An injury doing the tennis list item had required foot surgery.

When these things happened, I remembered a story I’d heard about horseshoes. In the West, horseshoes are hung with their ends pointed up, in the U shape, so your luck won’t spill out. They’re hung pointed down, in the arch shape, in the East, which says luck rains down upon you.

In Year Three, I chose to live like they do in the East—no longer clasping what I had for dear life, and opening my arms to give, with the faith that whatever I needed would be provided. And it was.

When we let go of what we think we must have in order to have value, we open ourselves up to making others feel valuable. Life is a doing thing, not a having one.

10. The hierarchy is a myth.

When I chose to live out my father’s dreams, I began seeing my life through the eyes of a man. Common expressions of inequity in my day-to-day life became more obvious. At one point, a man said, “I assume you’ve given up on having a family,” as though I’d been trying to have children and couldn’t. Our interview was about the respect he had for the legacy I was building for my father—that legacy didn’t have to be grandchildren. Each life has the ability to touch so many lives, in any way it chooses.

11. Wish well for others.

Around Year Three of my project, I noticed my peers buying new houses or having more kids or being promoted in their jobs. Even a new haircut could make me see green if I hadn’t been to the salon in 10 months because I was saving for Vienna. The list forced me to forego adult boxes I once checked, which made me worry I was being left behind.

But I realized it was better for me to support their success than envy it. By telling the universe I supported someone’s accomplishments, I was encouraging respect for my own.

12. Accept help.

We don’t have to be doing everything for ourselves all the time. When we let someone help us, we receive their love. I for one have noticed that every time my husband cleans the bathtub, he puts the shampoos back in completely different and yet somehow better spots. I both love and hate this. And am grateful I let him love me enough to do that. Among other, more important things.

I had to accept help from at least 54 people in order to accomplish 54 bucket list items.

13. If someone leaves you, don’t take it personally. They weren’t aligned with your story.

Sometimes people who promised to help with the list didn’t. In the past, I would have worried that they’d stopped liking me. But list items needed to be done, regardless. I’d remind myself as I watched the effects of the list on list helpers that not everyone was aligned with that. If someone changed their mind, I respected their choice.

Let yourself shine—doing so gives permission to others. But don’t expect everyone to bask in your light.

14. Inspiration is more effective than shame.

I learned this in Year Three, when I stopped lecturing people about their driving and started being the change instead. My life the past 6 years required a lot of travel, and not once did my phone get in the way. I was too busy having fun to need it. I was finally awake, and when you’re awake, you wake up others.

15. Stay who you were at age nine.

I often found myself, while researching list items, reading or watching things I wouldn’t normally. I felt nudged to read or watch whatever it was, and always found answers to questions I didn’t know I had.

When we follow paths fueled by instinct and hunches, we come closer to our real selves. We are expanding our worlds by expanding our minds. This kind of freedom is how progress happens. If you’re stuck with a creative project, you have to go where you wouldn’t normally go. You have to remember that feeling of being nine. When we write or make anything, we’re really just channeling. Open up your channels.

16. Vulnerability is strength.

I had to plow into uncharted territory, revisiting traumatic events, to write my book. But by letting myself go there and feel those feelings, I made it more possible to present my authentic self to the world, like I did as a child, when nothing painful had happened yet. When we stop hiding from remembered trauma, we let in more joy, because we create room for it. A life of hiding takes up too much energy to fully live.

17. Your life is your story to tell. Narrate it wisely.

One of the main reasons I needed to write a book about my relationship with my dad was because I wanted to rescript it. People offered up assessments of his life and his death that were too painful for me to believe. None of them were the person I knew, nor did they reflect all he’d given me.

I also couldn’t stomach being labeled a victim. We don’t become who we are because of what happens to us. We become who we choose to be. That’s what my father taught me.

We often need to reframe history to write our next chapter, to take what we’ve been through and insert it into a bigger story, one that includes both the bad and the good. Pretty soon, we see how the bad led to the good…and that there was so much more good after all.

When we choose to be our own narrator, we become the hero, too.