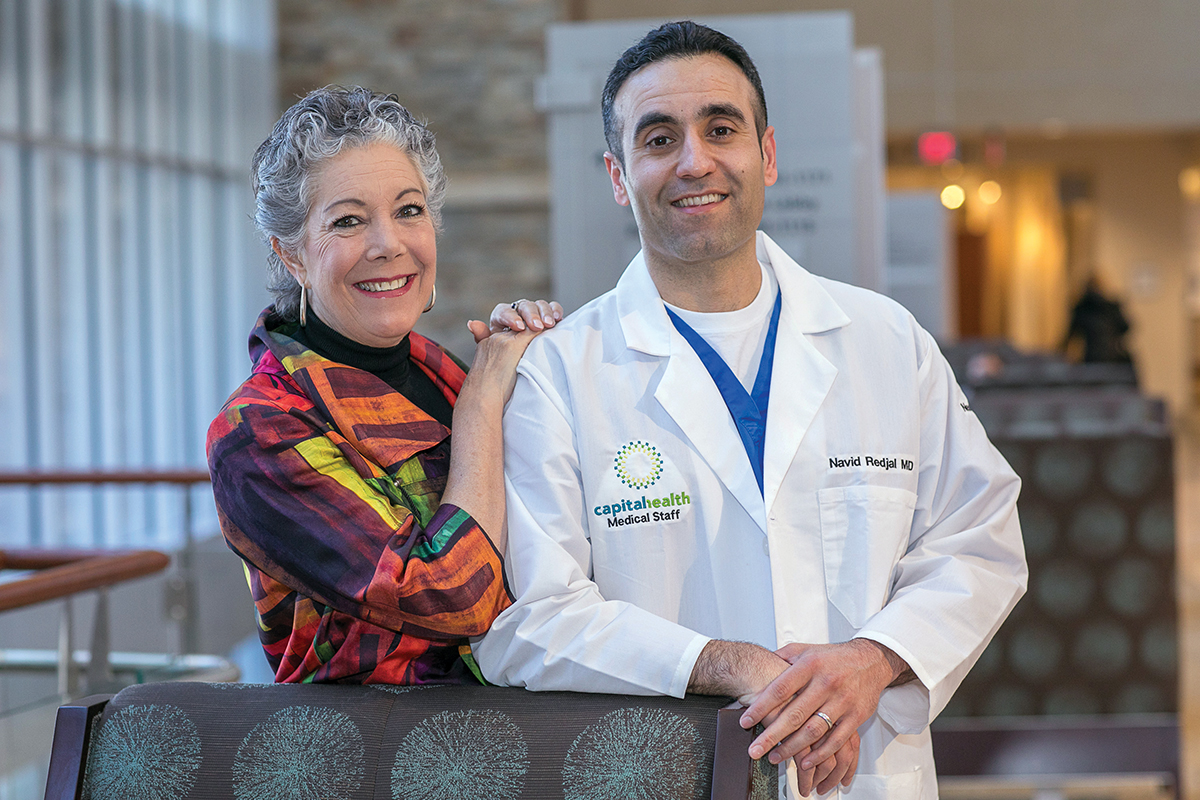

One morning last November, Kate Watson was straightening up her house. By late afternoon, she was considering awake brain surgery to remove a large tumor compressing critical brain areas. She shares her story, and Capital Health’s director of neurosurgical oncology takes us inside the latest approaches to tackling brain tumors.

If you were to draw a picture of the brain tumor an MRI revealed inside 61-year-old Kate Watson’s brain last November, you would make a chubby, peanut-shaped object, about the size of a lemon, a little to the left of the center of her head.

Kate’s tumor was large, and it resided in the left frontal temporal area of the brain known as Broca’s, which is responsible for speech production, and Wernicke’s area, which controls comprehension. She was already showing signs of its impact—when she came into the hospital for a concussion, she was confusing her words. “I had hit my head, and I told my friend that I didn’t feel a dent, but I was seeing straws,” Kate says.

Navid Redjal, MD, director of Neurosurgical Oncology at the Capital Institute for Neurosciences, explained that the tumor appeared to originate in the covering of the brain known as the dura. The tumor had compressed, and possibly infiltrated, critical speech areas of the brain. Although the tumor did not appear to originate from the center of the brain, it didn’t mean it wasn’t dangerous or even potentially deadly. “In the brain, the tolerances are small, the space is small, and anything that gets bigger can cause significant difficulties,” he says. “What matters is how the tumor is behaving.”

While the idea of an awake surgery can be unnerving to some people, Kate didn’t hesitate to choose it when the doctors presented her with options. “They said, ‘We can do traditional surgery, or we can do an awake craniotomy.’ I said, ‘Awake surgery. That’s what we’re doing,’ It was my immediate response. I knew I wanted to be awake and to give feedback during the surgery. I also had total faith in my team of doctors because I had seen their work before when a family friend needed surgery. Dr. Redjal and his team are so human. You can feel the compassion,” she says. “They had already gone way beyond the call. They were advocating for me well beyond the operating room.”

Dr. Redjal underscores his belief that the procedure was the best way to tackle the tumor without impacting brain function, specifically Kate’s speech. “With the awake craniotomy, we are able to constantly monitor her speech while at the same time removing as much of the tumor as possible,” he explains.

While there are some aspects of the surgery Kate doesn’t remember, she recalls each medical person in the operating room introducing themselves to her by name, explaining the role they would play during the surgery and how they would interact with each other. In the case of an awake craniotomy, the team includes the neurosurgeon, the neuro monitoring team, the neuro-anesthesiologist, the surgical physician assistant, and the OR nurse, all of whom play crucial roles during the surgery while they work to ensure that the patient’s brain function remains intact throughout. Neurosurgeons at Capital Health have tools, such as advanced brain mapping and intra-operative neuro-navigation, that allow them to stimulate areas of the brain while the patient is awake and create a map of areas that should be avoided during surgical resection.

After they properly numbed the area they would be operating on and provided the necessary level of anesthesia to keep her sedated but not unconscious, doctors put Kate under a tent with a nurse who would speak to her throughout the surgery and ask her questions when feedback was necessary to guide the surgeon. “She asked me things, like ‘What can you do with a shirt?’ Apparently, I gave a whole paragraph on dry cleaning and properly hanging up clothes,” says Kate.

From a medical standpoint, the purpose of keeping Kate awake and asking her questions that required that kind of response was to monitor her brain as they operated. “We can monitor cranial nerves, for example, when the patient is asleep, but speech is a very complex function that requires multiple different systems, and to really assess it, the patient has to be awake,” Dr. Redjal explains. “It provides us with real-time feedback and helps us gauge how aggressive we’re going to be in terms of resection. It helps us avoid permanently damaging the brain while we’re trying to cut away the tumor.”

Dr. Redjal and his team are so human. You can feel the compassion. They had already gone way beyond the call. They were advocating for me well beyond the operating room.

Understanding Terms

What is Glioblastoma?

Last July, Arizona Senator John McCain had a brain tumor removed that was an aggressive, highly malignant form of cancer known as glioblastoma. This form of cancer is known to spread quickly, and is often deadly because it’s associated with a network of blood vessels in the brain.

The American Cancer Society estimates that about 24,000 malignant tumors are diagnosed each year—about three in 10 brain tumors are glioblastomas. Since gliomas have often spread deep into the brain by the time of diagnosis, it can be difficult for the cancerous tissue to be completely removed.

What is Meningioma?

This is the most common type of tumor that forms in the head—it represents about a third of all primary brain tumors and occurs most often in middle-aged women. Meningiomas typically grow inward, causing pressure on the brain or spinal cord. While they can cause problems, they are often noncancerous.

How Is Brain Cancer Treatment Evolving?

Kate went home with her sister about 36 hours after her awake craniotomy. While she still struggles to follow some of the instructions to help her brain heal—avoiding reading for long stretches of time or really exercising the brain too rigorously—her overall prognosis is good. Less than 2 months from surgery, she still gets mild headaches and knows she’s not up for working a 40-hour work week at this point, but she feels grateful for the concussion that initially brought her into Capital Health in November and resulted in life-altering surgery.

While progress has been fairly slow in the area of primary brain tumors, or those that begin in the tissue in the brain, Kate’s treatment is indicative of the clearer understanding and advancement of tools that have been developed over the last half decade or so to avoid impairing the patient during surgery. “We understand it better, and we’re more careful about the impact on patients, as is shown by this case,” says Roy A. Patchell, MD, director of Neuro-Oncology at the Capital Institute for Neurosciences. “In the not-so-distant past, doctors would’ve just gone in and taken this tumor out. As a result, Kate might have had all kinds of bad effects from it and not come out of it in nearly as good of shape as she did.”

There are many reasons for the slow progress in primary brain tumor treatment, Dr. Redjal explains: “One reason is that the brain is very delicate, and you’re unable to perform some of the radical surgeries you can do in other organ systems in the body. The brain also has sensitivity to radiation that you don’t find in some other organ systems. Even chemotherapy is more challenging, as it has to get into the brain, and the blood/brain barrier keeps a lot of normal chemotherapy out. So, the types of medications that you can use are limited, and the response in the brain is more limited.”

However, while progress has been fairly limited in the treatment of primary tumors, which include glioblastoma multiforme (see sidebar on page 69), for example, the news has been better for metastatic tumors, which begin elsewhere in the body and then spread to the brain, spinal cord, or nervous system. These tumors are actually 10 times more common than primary tumors. “Over the last 50 years, there has been progress made in metastatic disease. When I first started in neuro-oncology, when somebody got a brain metastasis, more than half the people died quickly. That is now no longer the case because of treatment of the brain tumors,” Dr. Patchell explains. “While you don’t really cure people of their total cancer by doing well in their brain, you can certainly eliminate a lot of the bad side effects and the deterioration in the nervous system.”

In fact, Dr. Patchell was instrumental in alerting the medical world to the fact that surgery was effective in treating metastatic cancer, having authored a seminal paper that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine called “A Randomized Trial of Surgery in the Treatment of Single Metastases to the Brain.” At the time, radiation was the predominant form of treatment, despite the fact that it wasn’t all that effective on its own, Dr. Patchell says. The study compared the use of radiation on its own to the use of radiation plus surgery, with the latter proving to be the more effective treatment protocol.

Now, however, with advances in radiation treatment and its precise delivery methods, options like radiosurgery (such as the CyberKnife® at Capital Health) give patients greater options with fewer negative side effects.

Radiosurgery gives concentrated radiation in small areas and essentially destroys the tumor, in the same way that cutting it out with surgery would remove it, says Dr. Patchell. “With radiosurgery, you can hit tumors after they come back. Another benefit is that you may not really need whole-brain radiation therapy, which has long-term side effects and can impact people’s thinking,” he explains. “For small tumors, radiosurgery is the treatment of choice for most brain metastases. Surgery is still used, especially for larger tumors that are causing a lot of symptoms. Thanks to advances such as these, it’s rare that people die as a result of brain metastases anymore.”

On the whole, Dr. Redjal says the treatment landscape is more positive in that there are treatment options for patients who wouldn’t have had any decades or even years ago. Radiosurgery in particular gives doctors tools for improving quality of life or at least the chance to offer treatment without causing greater harm. “I think you can do things much safer now. For instance, we treat deep-skull-based tumors near the brainstem that are relatively small with radiosurgery. In the past, those patients needed to undergo surgery and would have to go through a lot,” says Dr. Redjal. “Now we’re able to treat lesions that are really deep within the brain with radiosurgery that would be relatively unsafe to treat surgically.”

While these kinds of treatment advances give hope to patients and doctors, both Dr. Redjal and Dr. Patchell temper their enthusiasm with a desire to offer patients options that will make a real difference in their lives. “Dr. Patchell and I aren’t into hype. Giving false hope to a patient is, in my mind, the absolute worst thing to do,” says Dr. Redjal. “We like to be realistic, we want the best for the patient, and we strive to do that.”