Women have long been chided for being too sensitive, chatty, and emotional, especially in the workforce. Now, more of us are realizing these traits can make us more effective employees and leaders—as well as better friends, lovers, and parents. The key? Learning how to effectively channel our feminine side. Here’s how we do it.

Wet, hot tears started falling down Amy Stanton’s face, and she knew she wasn’t going to be able to make them stop.

It was the most inopportune time to start crying: She was sitting at one of New York City’s fanciest restaurants, having an outrageously expensive meal with her boss—the president of the ad agency where Stanton worked. They were discussing her performance review, and the champagne flowed as they talked about Stanton’s stellar work ethic and the raise she was about to receive.

“It was a great review, but the raise wasn’t great,” says Stanton now, 20 years later and the president of her own public relations company. “And when I heard the number, I started crying.”

Stanton had a feeling the tears were going to make things uncomfortable, and sure enough, they did. “My boss walked away feeling like I was disgruntled, and I walked away feeling like she was so cold. And because I’d been trained that showing emotion like that was completely unacceptable in the workplace, I didn’t express why I was crying—I’d been busting my ass and expected more money—and we both left that lunch feeling awkward.”

It was one of those moments that would stick with Stanton, one part of the workplace persona she was learning to craft through experience and observation. She worked with a lot of men early on in her career and says she learned to believe that to thrive, she had to be more like them. “So, I put on this tough-girl armor,” she says. “That, combined with years of being told from a very early age that I was too emotional and sensitive prompted me to hide the more feminine parts of myself because I didn’t think they would serve me well.”

Jannell MacAulay, Ph.D., a retired U.S. Airforce Lieutenant Colonel who spent the majority of her career in male-dominated environments, can relate. “I think a lot of women are hesitant to show any emotion in the workplace because as soon as you do, you’re labeled in the extreme. If you show anger, you’re a bitch. If you show empathy, you’re a crier,” she says. “So, you learn to make adjustments in order to survive.”

However, once MacAulay became a commander, she started to let go of some of the expectations around how she should be and started being more authentically herself—even when it meant showing anger or sadness. “At some point, it just became too much work to not be authentically me,” she says. “It was liberating. And I became a way better leader.”

Once I started looking at my sensitivity that way, I stopped beating myself up for it and started celebrating it instead.

What's in a Word?

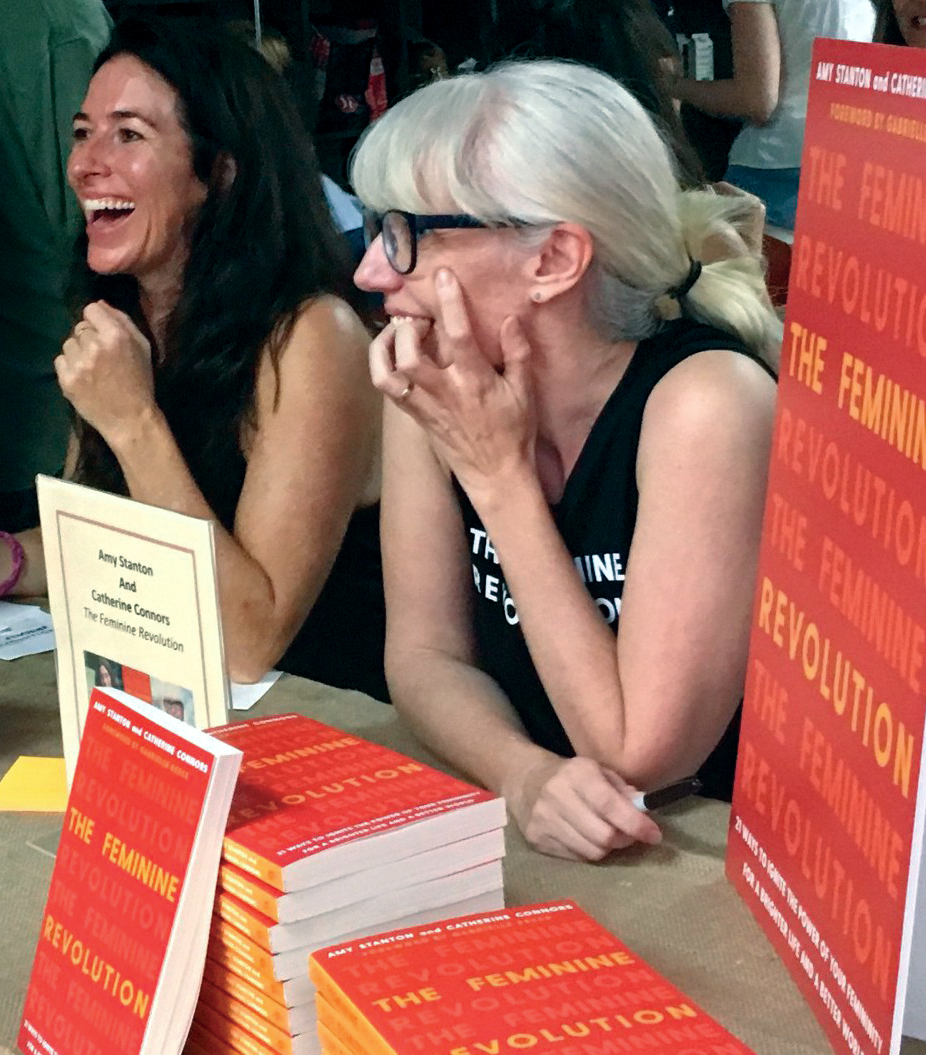

In Stanton’s book The Feminine Revolution, three incomparable women share their views on the concept of femininity.

“I don’t have a gut reaction to the concept of femininity. It would be like asking what my initial reaction is to the concept of height. And to assign it a positive or negative connotation is to mark it as either an asset or an affliction—neither of which I believe it should be. It’s part of who people are.” —Sela Ward, actress

“To me, femininity is owning your personal power in a way that feels true to you. And embodying it in a way that embraces the parts of the ancestral women before you with the parts of your own female heart that need to be heard and experienced for moments ahead. All that, and nightly bubble baths.” —Sara Bordo, CEO, Women Rising

“I am an example of what is possible when girls from the very beginning of their lives are loved and nurtured by people around them. I was surrounded by extraordinary women in my life who taught me about quiet strength and dignity.” —Michelle Obama, FLOTUS

I think a lot of women are hesitant to show any emotion in the workplace because as soon as you do, you’re labeled in the extreme.

Did We Squash Feminity in the Name of Feminism?

What both MacAulay and Stanton realized is that the message so many of us received as little girls—that femininity equals weakness in this world that rewards masculine stereotypes of power—needed a makeover. Stanton wrote a book to start doing just that.

In The Feminine Revolution, she and co-author Catherine Connors argue that one reason why we haven’t closed the pay or leadership gaps just yet is that we’ve been using a masculine playbook—one that tells us to get good and mad and to be tough and aggressive. It’s a “playbook that says power only looks like brute strength and dominance,” the authors write, and one that “asserts that femininity is incompatible with power—personal, political, or otherwise.”

Stanton wanted to ditch that old masculine playbook and create a new one that allowed her to take root in her femininity—not reject it. And she realized that in order to do that, she was going to have to do something pretty revolutionary: She was going to have to start urging all of us—women and men alike—to forget about our preconceived notions about femininity so that we could start to see it as powerful, not weak. And she was going to have to start with herself, re-framing some of her most feminine qualities as traits that would help her succeed, not shortcomings that would make her fail.

“I’ve always been really emotional,” says Stanton. “And my sensitivity was never something I felt I couldn’t bring fully to my work. Now, I realize this sensitivity and empathy I innately have is the reason I can sense what my clients need when we’re in the middle of a meeting, or why I can walk into the office and sense something’s up with one of my employees and address it.

“Once I started looking at my sensitivity that way, I stopped beating myself up for it and started celebrating it instead.”

For MacAuley, one moment in particular stands out as a lesson in how showing authentic emotion can be transformative for everyone. A few years ago, she was in charge of a unit of 400 airmen, one of whom passed away. “As part of my job as commander, I had to go down to this airman’s unit of 50 people and tell them he’d died,” she says. “I remember my initial thought was to not show any emotion. I thought I needed to be strong for these airmen.

“As soon as I shared the news of this young man’s death, the airmen crumbled to the floor in despair. And even though the military taught me to be stoic—that a leader operates from objectivity, and that you can’t let your emotions get in the way of your decision making—I realized that this crushing blow to us all had a lot of emotion behind it, and I couldn’t pretend I wasn’t sad, too. So I cried with them, right there on the ground. And what I learned was that my ability to do so was a strength.”

Unleash Your Feminine Side

Whether you’re hiding your feminine qualities, feeling bad about them, or some combination of the two, here’s how to start to ignite the power of your femininity so you can show up at work—and in all aspects of your life—as more authentically you.

Unpack your baggage of feminine stereotypes. Maybe you’ve been taught to believe that strong women don’t cry or show weakness. Perhaps you’ve picked up on messages that in order to succeed, you have be less apologetic or better able to brush off the tough stuff. Take a moment to consider: Could these “weaknesses” actually be powerful assets? Could your tears be a sign of how deeply you care about your work and your colleagues? Is it possible that your instinct to apologize or your tendency to engage actually create more respect and powerful bonds among your co-workers?

“When you really look at feminine characteristics, nothing inherent to them makes them weak,” says Stanton. “It’s their association with the condition of girlhood or womanhood that makes them problematic. If a man adopts those traits, they become powers.” Once we can start to fix these stereotypes and send our daughters different messages, we’re in a better position for these traits to become powers for us, too.

Understand the difference between emotions and being emotional. One of the first things MacAuley teaches in her role as a leadership and performance coach is this distinction. “It is 100 percent human to have emotions,” she explains. “It’s what makes you relatable as a teammate or a leader. The important question to ask yourself is this: Are your emotions driving your behavior? When that happens, you’ve become emotional.”

Take, for example, frustration. It is valid to feel frustrated when someone does something to upset you, whether it’s a co-worker who won’t listen to your thoughts on a project or your toddler who won’t put his shoes on. In an ideal situation, says MacAuley, you’ll acknowledge the emotion and then make a rational choice about how you’re going to respond. “The potential problems start to emerge when you let the emotion drive your behavior, which may lead to saying something rude in a meeting or lashing out at your kid.”

Bottom line: You’re going to have emotional reactions to all sorts of situations, in all areas of your life. Rather than trying to shove those feelings down because you think you should, work on rational responses rooted in your emotions.

Use mindfulness tactics to boost your self-awareness. One of the simplest, yet most effective strategies for being more authentic is to learn how to become truly present. When you do this, you increase your self-awareness, which tees you up to act from your most genuine place.

“When you’re in the mind-wandering haze inside your head, thinking about all of your to-dos and catastrophizing about your stressors, you’re consumed with all of the things you think you should do,” says MacAulay. “When you’re in the present moment, you can remember who you are and what you believe in and let that guide your decisions and behaviors.”

Sure, things like yoga, meditation, and other mindfulness-based practices can help you practice operating from the present moment. So can doing something as simple as calling to mind an image of your happy place—a scene or moment in time that makes you feel calm and content. For MacAuley, that image is of her family, and when she finds herself tempted to do something because she thinks she should, she tries to anchor her breath on an image of her husband and two kids. “Doing this instantly brings me this sense of clarity,” she says. “It helps me get out of my head, into the present moment, and better able to accept and embrace all of me.”