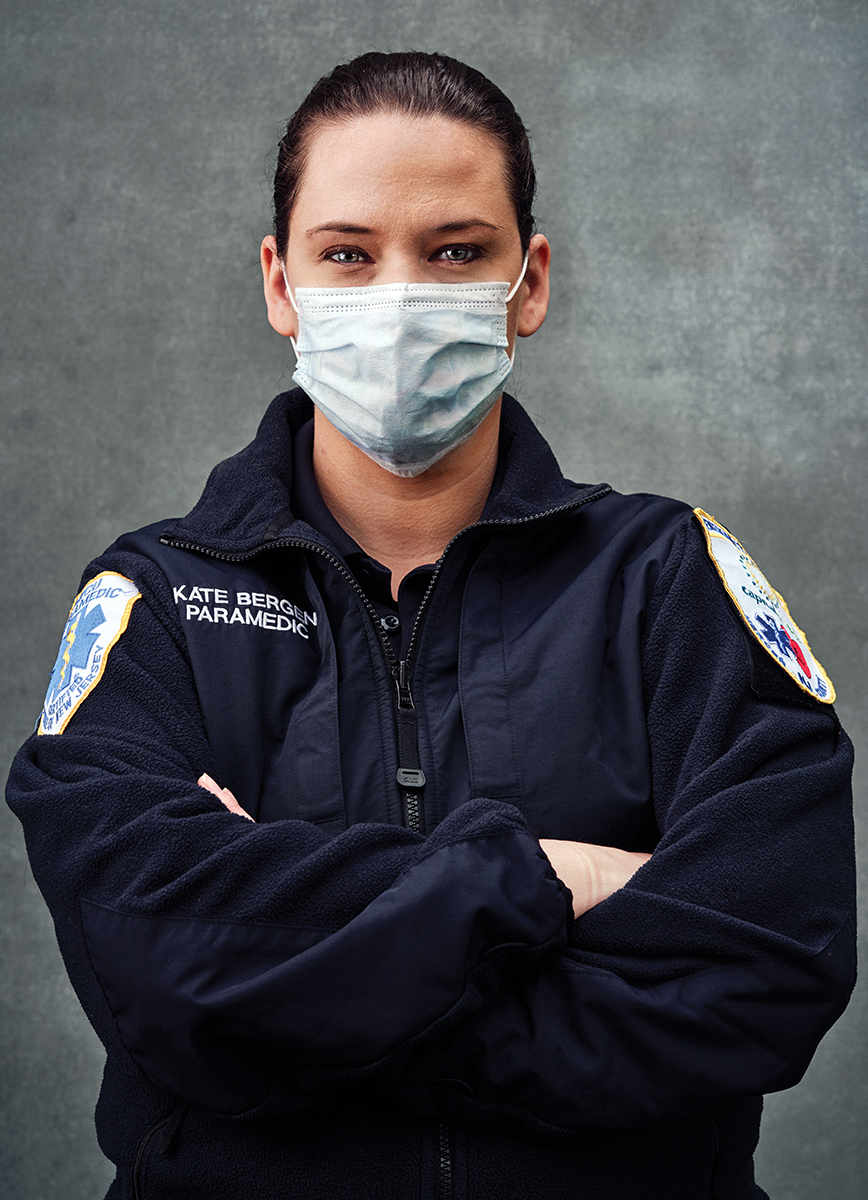

As a paramedic transporting some of the sickest COVID-19 patients to the hospital, I worked on the front lines of the war against this disease. This is what I’ve seen during the pandemic and how I find solace and purpose by painting.

I slide the goggles over my eyes and pull up my respirator mask, both grateful for this protective equipment and also dreading how it’ll make me feel all day: hot, sweaty, and increasingly anxious. I’m a paramedic, which means I’m at the very front of the front lines of the fight against COVID-19. I know this personal protective equipment (PPE) is my armor.

Yet, just because this PPE offers me protection doesn’t mean it’s foolproof, and the longer I’m in my respirator, the faster my heart races and the shorter my breath becomes. When I take it off at the end of the day, I’ll have this feeling of wanting to crawl out of my skin. And the deep indentations the goggles and respirator leaves on my face will take hours to go away—a reminder as I look in the mirror brushing my teeth before bed that I’ve been in direct contact with the thing that the rest of the world is trying to avoid: the novel coronavirus.

I had to straddle a fence no health care worker should ever have to: How far can I go to give this patient effective care while not putting myself in direct contact with a deadly virus?

I Run in When Everyone Else Runs Out

I’m trained to do the work that I do, and I’m grateful to be able to help those who need it most. But trust me when I tell you this: This disease is every bit as harrowing as you’ve read about.

I’ll never forget one shift I worked toward the end of March, as the number of COVID-19 cases was really picking up. We kept getting calls from the same nursing home. We picked up a patient who was so sick—his breathing was too fast, oxygen saturation far too low, and the sounds coming from his lungs were downright scary. When a patient presents these kinds of symptoms, we’d typically use a nebulizer to deliver medication. It’s like a medical-grade inhaler that turns liquid medicine into a mist. But we couldn’t do that because the coronavirus travels through aerosols, and that treatment would’ve meant risking exposure to those of us trying to treat him.

All we could do was throw on the sirens and lights and get that man to the hospital. It felt like the longest journey. I had to straddle a fence no health care worker should ever have to: How far can I go to give this patient effective care while not putting myself in direct contact with a deadly virus? All of our rules and guidelines—protocols that have always been black and white—were suddenly gray. And just after we dropped that patient at the hospital, we had to turn around and head straight back to that same nursing home for another patient presenting with the same life-threatening symptoms.

Every day, I worry about the severity of the virus and the speed at which it travels. What we know for sure is that COVID-19 doesn’t play favorites. I’ve taken young, healthy patients in their 30s and 40s to the hospital who never made it out. I’ve treated countless older people, some of whom have succumbed to this virus and others who’ve won their battle against its attack on their lungs. I’ve pronounced more patients dead in the last few months than in my entire career. Even harder is telling a family member that his or her loved one has passed away—and having to do that while wearing my respirator. I feel like Darth Vader, unable to share the full expression of empathy and sadness on my face, resisting the urge to touch that grieving person’s arm to let her know I really do care.

As a paramedic, I’m essentially a mobile emergency room, doing whatever I can to help keep patients alive as we transport them to the hospital. During the coronavirus pandemic, there have been too many cases where I can’t do anything for patients because they’re so very sick. Some of them have all of the symptoms of COVID-19, but they’re in critical condition because they’ve waited too long to get help. Others are dealing with something that isn’t COVID-related, but they’ve also put off getting treatment longer than they should have because they were scared of being exposed to the virus.

As I treat these patients, it’s not lost on me that the kind of care they need is prompting me and my coworkers to risk our lives, too. In a job that is already stressful, this is an added weight that often feels like too much to bear. I’m committed to doing everything I can to help every single one of my patients. But that means every single day I’m terrified that I’ve been exposed to COVID-19—and even more afraid that I’ll bring it home to my husband and our babies, 3-year-old Jase and 20-month-old Maverick.

Sometimes, the thought of exposing my family to this virus fills me with so much dread that I get a little dizzy, and my fingers and toes get tingly. I ask myself again and again, Did I wash my hands well enough? Did I clean as meticulously as I could? I start breathing faster, almost to the point of hyperventilating. I know these are signs of a panic attack—something I’ve seen countless patients deal with and have helped talk them through. But now it’s happening to me, and I am realizing for the first time how awful it feels.

Sometimes, the thought of exposing my family to this virus fills me with so much dread that I start to get a little dizzy, and my fingers and toes get tingly.

Outlets for Anxiety

My husband is an intensive care unit nurse, which means he is also exposed to COVID. He’s been my rock—not only someone I can lean on for support but also someone who really gets it. He’s seeing the same devastation I’m am, and he’s holding the same kind of worries about our exposure and transmitting this virus to our kids.

We make it a point to connect every night after work, even when we’re bone-tired. We talk about our patients from the day. We remind each other that we’re still healthy and that our kids are, too. We share this sense of gratitude for the fact that we’re still working and have a house over our heads and food on our table. Not every family is so lucky. And we even recap all of the things we’re doing when it comes to following proper hygiene protocol, almost like our own checklist of all the steps we’re taking to stay as safe as we can throughout this pandemic. We’re both filled with fear. But we’re doing our best to manage it so we can show up for each other, our kids, and our patients.

We’ve always channeled the stresses of our jobs in health care through art. My husband does metalwork, woodworking, and other forms of physical crafting, and I’ve always painted. And I’ve found myself more drawn than ever to our little art studio in the garage. It’s been a way to process all of the emotions that have come up for me during this time—and my painting has taken on a new meaning, both figuratively and literally.

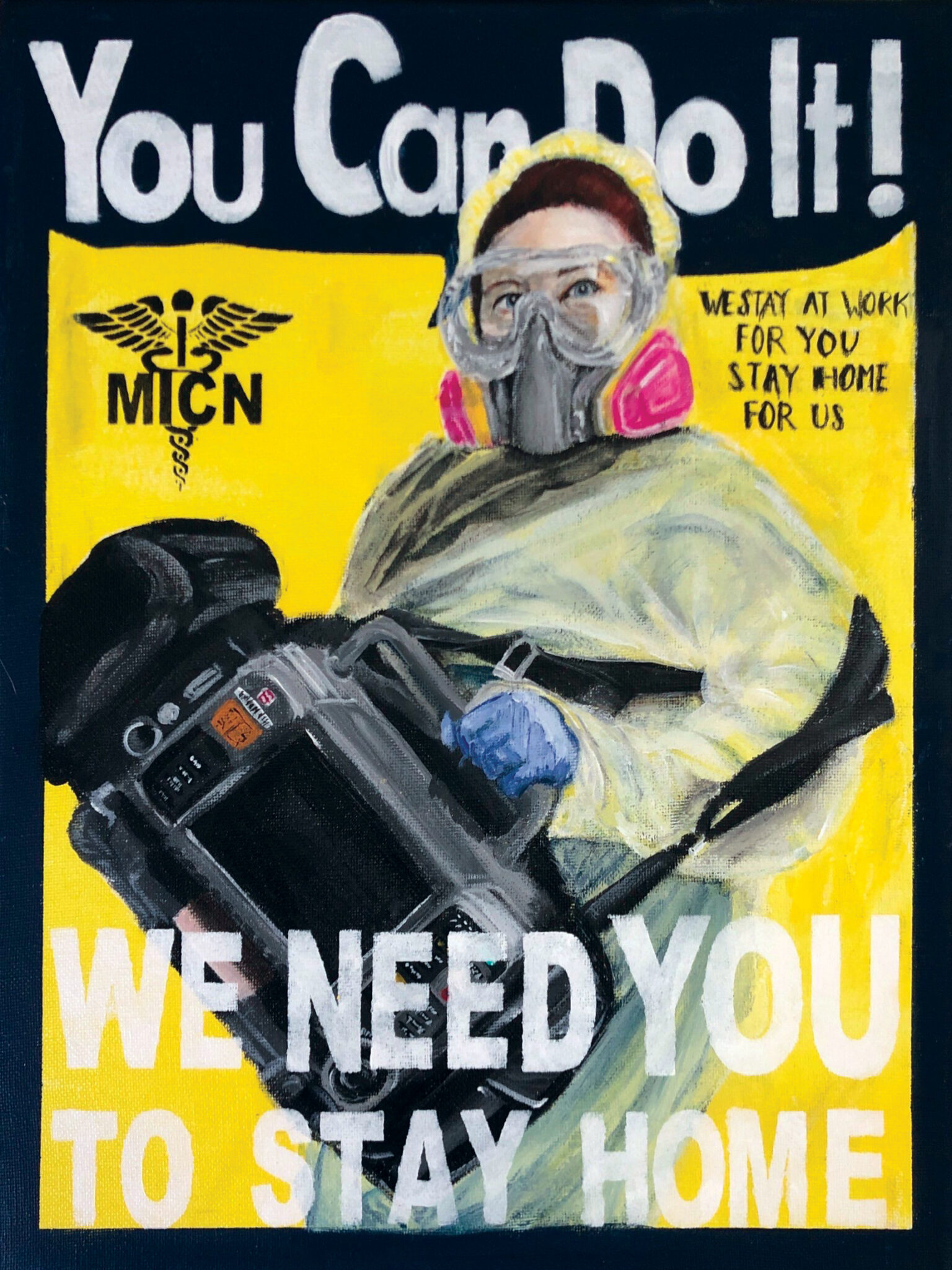

Years ago, a friend showed me a picture of “Wendy the Welder”—the lesser-known cousin of “Rosie the Riveter.” Both Wendy and Rosie were the spotlights of propaganda paintings done during World War II, when more than 18 million women across the country were enlisted in the steel mills, automotive plants, and shipyards of America to work traditionally male-dominated jobs in an effort to support the war. When I first saw Wendy, I did a double-take. It turns out my friend showed the painting to me because I look like her, and it’s true! I felt this immediate connection like if I were alive back in the 1940s, I would’ve been one of the women to step up and do something. I would’ve been a Wendy, welding battleships, or a Rosie, riveting fighter planes. It’s just my nature.

When I turned to my paintbrushes and canvases to start painting in an effort to find some solace during the height of the coronavirus outbreak—arguably the most stressful period of my career and a time when all Americans were being asked to stay home for their country—I couldn’t stop thinking of these WWII-era women. So, I took a picture of myself in my respirator mask, drew a sketch of it, and started painting. I started thinking of it like Rosie the Riveter meets Uncle Sam. At the top of the painting I wrote, “You Can Do It.” At the bottom, I wrote, “We Need You to Stay Home.”

The more I painted, the more I wanted to pay homage to those WWII posters. Because I feel like I’m at war. It’s not something I ever expected. Yet, here I am on the front line, hoping today isn’t the day I bring home something that could be fatal.

While my paintings can’t take away the danger inherent in what I’m doing, I hope it shines a spotlight on the lesser-known heroes who have made a real difference in helping us get to the other side.

My Call to Inaction

My paintings became a call to action—a call to inaction, really. I want as many people as possible to realize that if you’re not an essential worker, you need to stay home. I believe that’s the only shot we have at winning this war we’re fighting, and it’s the best way to show support for all of the essential workers risking their lives. That includes those of us who work in health care, and also the grocery store workers, firefighters, garbage truck drivers, and so many other people ensuring some semblance of life as we know it can go on.

Once I finished that first painting, I couldn’t wait to do more. Next, I painted a friend of mine who’s a nurse. She’s Asian-American and has experienced discrimination because small-minded people have called the coronavirus “the China virus.” I am committed to showing everyone that those people who are being harassed right now are the same people here on the front lines! And I am committed to representing women who feel under-represented—truck drivers, custodians, mail carriers, and even a Wawa employee.

Without question, this art is an outlet for my stress and anxiety, and a way to channel some of my anger and fear into something that might actually do some good in the world. But what I’m learning is that this art is also for those women I’m representing—for everyone right now risking their lives and the health of their loved ones for others.

What I’m doing doesn’t change the fact that all of us on the front lines could die. We are putting ourselves and our families in harm’s way. But while my painting can’t take away the danger inherent in what I’m doing, I hope it shines a spotlight on the lesser-known heroes who have made a real difference in helping us get to the other side. I hope it inspires others to take what we’re doing seriously—and help us by staying home.

To see more of Kate Bergen’s art, visit her website.