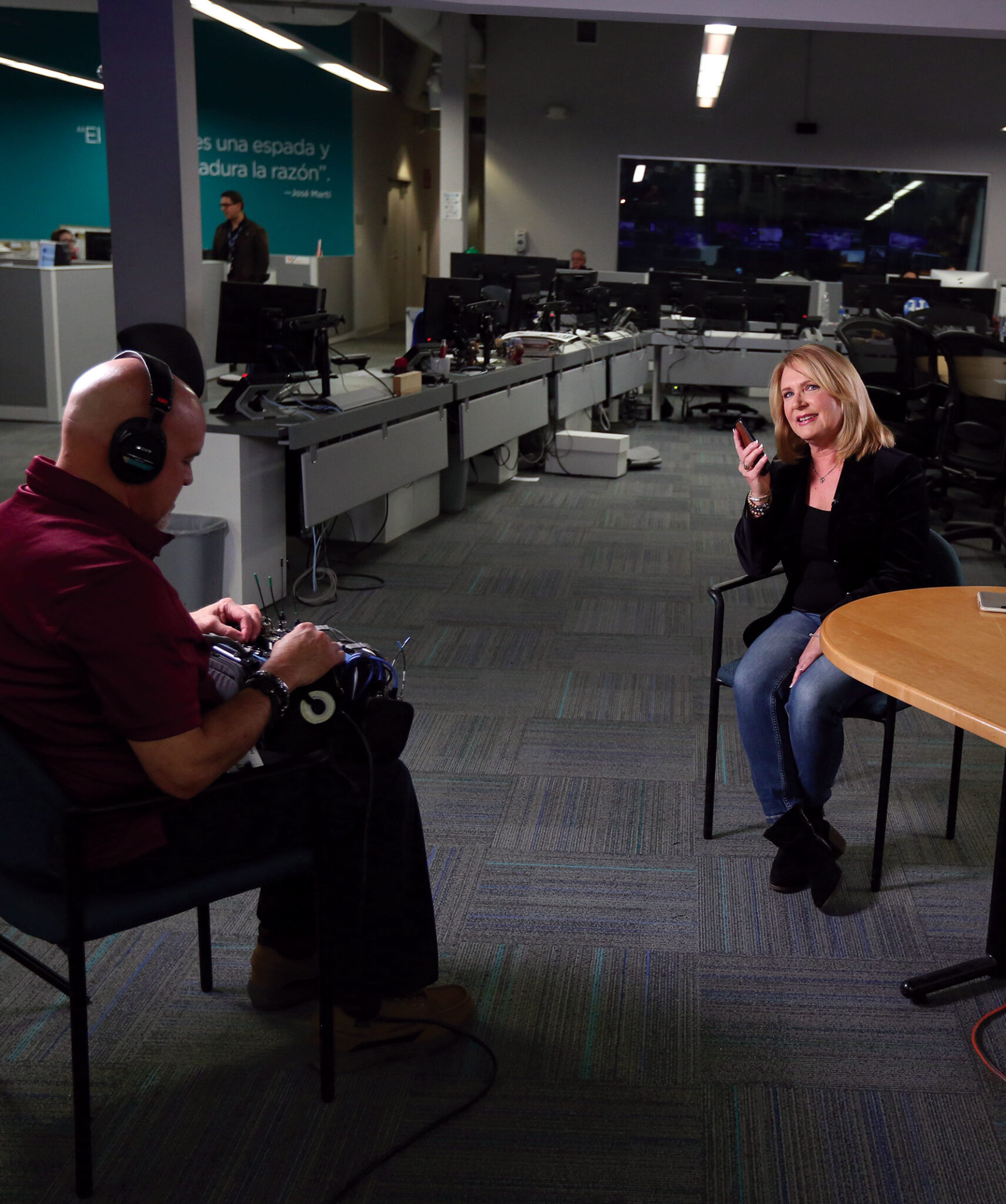

Raised in the Philadelphia area, investigative reporter Julie K. Brown wrote a three-part series for the Miami Herald that broke the Jeffrey Epstein story wide open and changed the course of history.

Did the Sixers win last night?”

Julie K. Brown hasn’t lived in the Philadelphia area in decades, and yet upon starting a phone conversation with someone from the 215 area code, the first thing Brown wants to know is how the local NBA franchise performed and what in the world the organization is going to do with Ben Simmons. You can take the girl out of Philly but…

Actually, in this case, it’s a very good thing you can’t take the Philly out of the girl. You may not know Brown by name, but odds are you are familiar with her work. She, along with Miami Herald colleague Emily Michot, blew open the case of the prosecutorial misconduct that allowed Jeffrey Epstein to continue to sexually abuse young women long after he should have been jailed. Her three-part series in the newspaper led to the financier’s 2019 arrest on multiple sex trafficking charges, the resignation of U.S. Secretary of Labor Alexander Acosta, who, as a Miami prosecutor, gave Epstein immunity against the same charges, and the arrest of Epstein’s partner, Ghislaine Maxwell, whose trial started last November. Above all else, it gave a voice to the victims, who for years were discredited and silenced. Brown, who won multiple awards for her three-part series on Epstein, explains the painstaking process in her book, Perversion of Justice.

If you ask Brown, she’ll credit her Philly upbringing for the grit and determination that was required to fight through the obstacles on her way to reporting the story and the stomach-churning aftermath that came later. Her life made her both empathetic to the eventual victims who would lead to the demise of Epstein and disgusted with a system that allowed a predator to continue to abuse because his wealth and connections afforded him an otherwise unheard-of plea deal. Brown’s childhood imbued her with a need to pursue righteousness. Suburban Philly gave her a blue-collar work ethic. And working in the city earned her the necessary journalistic chops. “This business really kicks your ass—women in particular,’’ Brown says. “But I believe, as simple as it sounds, if you want something badly enough, you find a way. That was me. It may sound a little corny, but I wanted to change the world.’’

For the young girls upon whom Epstein preyed, she certainly did.

This business really kicks your ass—women in particular. But I believe, as simple as it sounds, if you want something badly enough, you find a way. That was me. It may sound a little corny, but I wanted to change the world. That’s why I pursued this career.

Everything I did in my career prepared me for this story.

I could never have done it earlier in my career. Everything I did prepared me to have the muscle to do this.

Philly Roots

The daughter of a single mother, Brown grew up practically on her own, her mother working so many hours she rarely had time for her three kids. Yet the effort never seemed to pay off. Brown remembers coming home to an empty house, the furniture repossessed rather than the utilities turned off—a twisted attempt from the electric company at humanity. Teased and ridiculed for what she didn’t have by her wealthier Bucks County peers, Brown understood from a young age that money was a great separator. She was a good and dedicated student, but it didn’t matter. Her family lacked, and therefore she was an outsider.

Brown left home at 16, emancipating herself from her mother and living with older friends. She took what jobs she could—including a stint at a local lampshade factory—while simultaneously going to high school, all with the sole purpose of somehow getting to college. She earned a scholarship to Temple University, unsure of exactly what direction she might take. A journalism professor saw promise in her work, shepherding her toward a career that she discovered truly suited her. Brown saw it as a noble profession, a chance to shine a light on the tilted system she herself witnessed growing up. “You get pulled over for a speeding ticket, and it’s $300,’’ she says. “That doesn’t faze people with money, but for some people, that means you can’t pay for your groceries that week. It pissed me off. I wanted to fight the power.’’

Brown graduated magna cum laude from Temple, but like so many in the business, her career was more a slow climb than a rocket launch. She approached it much like a star student who opts to sit in the front of the class, determined to be a diligent reporter who never turned down an assignment and grateful for whatever job she had. She covered the police beat, wrote obituaries, and worked at the hyper-local Lambertville Beacon, as well as the suburban daily, Bucks County Courier Times. That doesn’t mean she didn’t have aspirations. She dreamed of getting a job at a big metro paper and nearly gave up and pivoted to public relations when it took a little longer than she’d hoped. Instead, a mentor convinced her to stay the course, and Brown finally landed at the Philadelphia Daily News, a tabloid known for its willingness to fight for the little guy.

With two kids of her own by then, she switched her schedule and worked nights. It made for long days, but the tradeoff was worth it. Brown got to be home with her children, a time she relished, having missed so much of her own mother growing up. It also was a blissful time for newspapers, before the Internet shook the business model and reporters turned into cost-cutting liabilities. The Daily News competed head-to-head with the more stately Inquirer, and reporters within the newsroom competed hard with one another for the best stories. Yet there was a sense of collegiality, too, Daily News reporters proud of their spunky reputation. They toiled in the basement of the North Broad Street office building while the Inquirer folks claimed the top floors. They found a purpose in their metaphorical underdog status.

The job also allowed Brown to pursue her seemingly idyllic dream to hold people in power accountable. She was dogged, fearlessly going into the city’s worst neighborhoods to find the families of murder victims and tell their stories, determined to make the victims more than just a statistic. Brown also fought against corruption and cover-ups. Her coverage of firefighters infected with Hepatitis C helped force mandatory testing for public safety workers.

In 2006 she moved to Miami, hired at the Herald initially as an enterprise editor. She admits she questioned her sanity. She loved the Daily News, loved Philly, and was going through a divorce, checking just about every do-not box for sweeping life decisions. But by then, the newspaper business already had turned dicey, especially for the Daily News. Starting that year, the paper would go through a series of new owners, rumors of its demise always circulating. Chased by memories of her own austere childhood, Brown opted for the stability that the Herald offered. Plus, the city’s juxtaposition of opulent, pink-flamingoed wealth and gritty city underbelly suited Brown journalistically. She quickly moved out of her editor role and into a reporter position, in part because she missed being boots on the ground but largely because she thought she’d be more useful as a reporter, and thereby guarantee job security.

The Big Dig

Brown lent her journalistic skills to anyone at the paper who needed them—she even helped investigate baseball player Alex Rodriuguez use of steroids. Her primary beat, though, was covering the prison system. She would win a George Polk Award for her investigation into the women’s prisons there. That story, on female inmates forced to have sex with prison guards, piqued her curiosity about sex trafficking. Through the inmates, Brown came to understand how women, stripped bare of their value, often were forced into such situations. She believed there was more to the story.

As she researched, one name kept popping up: Jeffrey Epstein. By then people not only knew about the financier, but he’d already been through the legal system. Originally investigated in 2005 after a parent complained he’d sexually abused their teenage daughter, Epstein was given what’s called an NPA—a non-prosecution agreement. He was required to pay financial settlements to several victims and register as a sex offender and serve 13 months in a work-release program. He could have been given a life sentence. Acosta, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Florida, oversaw the deal.

It was a ridiculously cushy punishment for a sexual predator, and when Acosta was named as then President Trump’s choice for secretary of labor, Brown wondered how the women who had been abused by Epstein might feel about it. She tossed the idea to her editor, thinking of it merely as a complementary piece to the broader story about the former Miami attorney’s possible appointment to the federal position. “I wasn’t thinking about exposing anyone. Plenty had already been written about what Epstein had done,’’ Brown says. “The women’s voices were missing. That was my sole motivating factor.’’

As soon as she dug into the files, she realized she was onto something bigger. The documents showed a pattern of betrayal, by lawyers as well as state and federal prosecutors, who not only gave Epstein the deal but continued to ignore complaints against him, as well as his lawyers’ attempts to intimidate the women he abused. Hundreds of people, Brown discovered, had to look the other way to allow Esptein to continue, all complicit if not guilty in his crimes. The system, she saw, had failed horribly.

The final product of a piece of investigative journalism dropped into the world with a splash, with headlines and gut-wrenching details that begged for reaction may be rewarding, but the work to get there is far from glamorous. It is, in fact, arduous, requiring poring through thousands of pages of documents, all written in (sometimes redacted) legalese, searching for sources, earning their trust, corroborating stories, and painstakingly fact-checking every detail to protect both the reporter and the newspaper from lawsuits. It can take months, even years, and takes a special sort of reporter, one not stymied by dead ends or interference. “Everything I did in my career prepared me for this story,’’ Brown says. “I could never have done it earlier in my career. Everything I did prepared me to have the muscle to do this.’’

Brown is quick to point out that she did not break the Epstein story. She likens herself instead to a cold case detective, who was able to take all of the information already gathered—from the FBI, the state attorney’s office, lawsuits, her own interviews with detectives, and police reports—and get a helicopter view of a very complicated puzzle. She did not find the final piece—who it was that actually agreed to give Epstein the sweet plea deal that let him continue for so long—but she found enough to shed light on what had happened, and what’s more, the damage it had caused.

Fighting for the Victims

Brown’s journalistic skills, however, weren’t the only tools she brought to the investigation, and at some level, not even the most important. Her own life gave her compassion that the women had not experienced from other reporters. She understood how it felt to be marginalized and dismissed because of what you didn’t have, or how a child, raised by well-intentioned parents whose only crime was that they had to work so much that they couldn’t be present all the time, grew into easy, vulnerable prey for people who seemed to offer them the world. Brown herself was lucky. She had older friends who helped her where her mother could not and protected her when she left the house. But she understood why so many others weren’t so lucky.

And so for the victims, most now in their 20s and 30s, here came a woman who saw them. So much of the coverage had been salacious—about the tawdry visits to Epstein’s private island and the famous people who were in his circle. Brown cared about the faceless and unnamed victims whose lives had been upended by Epstein and by the legal system.

Brown didn’t question why they went back to Epstein—even as some of her editors pushed back on that very question. She understood what grooming was, how the girls with nothing had been lured by a man with everything. “You know you shouldn’t go back, but that person is your life raft,’’ she says. She brought that humanity with her when she contacted the victims by letter and let it guide her as she earned their trust and, ultimately, as they told their stories. The interviews left Brown emotionally ragged and yet inspired to go on. “They were so damaged,’’ Brown says. “They were betrayed over and over by the system, by Epstein, by lawyers. They had been through so much, and the power of the series was everything that they’d been through because of it. It wasn’t looking at what he did, but how what he did and what the prosecutors did, or didn’t do, damaged these girls for life.’’

Brown started digging in on the Epstein story in March 2017. On November 28, 2018, the first story in the series was published. Brown didn’t sleep the night before. She fretted for her kids—she knew she’d been followed by investigators hired by Epstein—but mostly she worried that the story wouldn’t resonate, that the victims’ voices wouldn’t be heard. She was wrong. The series and her subsequent follow-up reporting led to Epstein’s arrest, as well as Acosta’s resignation. She won several awards for her work. She wrote the book, which became a New York Times bestseller, as sort of her own testimony, explaining how she did the work but also digging into the parallels in her own life that allowed her to see what others had missed.

Brown laughs, though, when asked if her life has changed dramatically. She is more financially stable than she’s been before in her life—but when the low bar is set at biweekly visits to check-cashing agencies and fears of car repossession, there is really nowhere to go but up. “I’d love to say I made a ton of money and I don’t have to work again, but that’s not the case,’’ she says. “I came from such a deficit situation.’’ In fact, she recently returned to the Herald after taking a leave to promote the book. Now 60, she is grateful to have the job but also well aware that, despite the notoriety, nothing has changed. She will have to work to keep a career alive in a business that remains under threat. Brown figures her job will be much the same as it had been before, a mix of breaking news and projects. She does not expect to be treated as some sort of star. Which is just fine with her. Brown hardly sees herself as one, anyway.

Brown flew home to Philadelphia recently. Her daughter is living in Delaware County, and while Mare of Easttown might have made Delco famous, Brown doesn’t know the area well. She poked around, learning her way here and there, eventually landing at the mecca for all Philadelphians. “Ah, I just loved to be able to go into Wawa and get my coffee,’’ she says.

You can take a girl out of Philly. But don’t you dare take the Philly out of the girl.